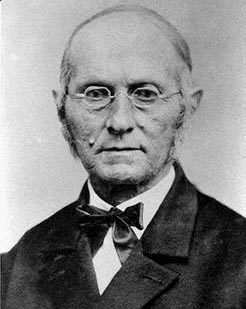

Joseph Bates 1

INCIDENTS OF MY PAST LIFE. NO. 2.

THE CABIN BOY AND THE SHARK.

My first European voyage from New York to

London and back, opened new scenes before me,

not uncommon to a sea-faring life.

One circumstance occurred on our homeward

voyage some eighteen days after departing from

Land's End, of England, which I will here relate,

In the morning, (Sunday,) a large shark was

following us. A large piece of meat was fastened

to a rope and thrown over the stern to tempt

him to come up a little nearer, that we might

fasten to him with a barbed iron made for such

purposes; but no inducement

of ours seemed to affect him. He maintained

his position where he could grasp whatever fell

from either side of the ship. A SHARK is a voracious sea-fish.

On such occasions the old stories about sharks

are revived. How they swallow sailors alive, and

at other times bite them in two, and swallow

them at two mouth-fulls, &c. They hear so much

about them that they attribute more to their

sagacity than what really belongs to them. It is

said that sharks have followed vessels on the

ocean for many days when there were any sick

on board, that they may satiate theirvoracious

appetites on the dead bodies that are cast

into the sea. Sailors are generally brave and

fearless men; they dare meet their fellows in

almost any conflict, and brave the raging storms

of the sea; but the idea of being swallowed

alive, or even when dead by these voracious

creatures, often causes their stout hearts to

tremble. Still they are often credulous and

superstitious.

Towards the evening of the day referred to, when

we had ceased our fruitless labors to draw the

shark away from his determined position astern

of the ship, I ascended to the main-top-gallant

mast-head to ascertain if there was any vessel

in sight, or anything to be seen but sky and

water. On my way down, having reached about

fifty feet from the deck, and sixty from the

water, I missed reaching the place which I

designed grasping with my hand, and fell

backwards, striking a rope in my fall which

prevented my being dashed upon the deck, but

whirled me into the sea. As I came up on the top

of the waves, struggling and panting for breath,

I saw at a glance the ship (my only hope) was

passing onward beyond my reach. With the

encumbrance of my thick heavy clothing, I

exerted all my strength to, follow. I saw the

captain, officers and crew had rushed towards

the ship's stern. The first officer hurled a coil of

rope with all his strength, the end of which I

caught with my hand. He cried out, "Hold on!" I

did so until they hauled me through the sea to

the ship, and set my feet upon the deck.

To the question if I was hurt, I answered, "No."

Said another, "Where is the shark?" I began to

tremble even as they had done, while they were

in anxious suspense fearing he would grasp me

every moment. The thought of the shark had

never entered my mind while I was in the water,

I then crossed over to the other side of the ship,

and behold he was quietly gliding his way along

with us, not far from the side of the vessel,

seemingly unconscious of our gaze. And we did

not disturb him in any way; for the sailors and

passengers were all so glad that the cabin-boy

was rescued, not only from a watery grave but

from his ferocious jaws, that they had no

disposition to trouble him. He was soon missing

and we saw him no more. But the wonder to all

was, how he came to change his position to a

place where he could neither see nor hear what

was transpiring on the other side and stern of

the ship. Surely Noah's and Daniel's God was

there! The very same God that so recently

commissioned the Advent Angel [Rev. x] to

proclaim to all on land and SEA that Jesus

the Messiah is coming, A second, and then a

third following them, saying, "Here are they that

keep the Commandments of God, and the faith of

Jesus."

Dear children, if you have a desire to join this

highly honored, home-bound company, and be

forever saved in the kingdom of God, lay fast

hold of the rope, and HOLD ON!

JOSEPH BATES.

Battle Creek, Michigan

INCIDENTS OF MY PAST LIFE. No, 3.

THE SAILOR BOY AND ISLANDS OF ICE.

PROCEEDING on another voyage from New York

to Archangel, in Russia, about the middle of May,

in the afternoon, we discovered a number of

islands of ice, many of them appearing like large

cities. This was an unmistakable sign that we

were nearing the banks of Newfoundland, about

one thousand miles on the mariner's track from

Boston to Liverpool. These large masses, or

islands of ice, are driven by wind and current

from the ice-bound regions of the North, and

strike the bottom more than three hundred feet

from the surface of the sea, and some seasons

they are from two to three months dissolving

and tumbling to pieces, which lightens them, of

their prodigious burdens, and thereby are driven

onward over this deep water into the fathomless

part of the ocean, and are soon dissolved in

warm sea water. A strong westerly gale was

wafting us rapidly in our onward course, and as

the night set in we were past this cluster. The

fog then became so dense that it was impossible

to see ten feet before us. About this time while

one W. Palmer was steering the ship, he

overheard the chief mate expostulating with the

captain, desiring him to round the ship to, and

lay by until morning light. The captain deemed

we were past all the ice, and said the ship must

continue to run, and have a good lookout ahead.

Midnight came, and we were relieved from our

post by the captain's watch, to retire below for

four hours. In about an hour from this we were

aroused by the dreadful cry from the helmsman,

"AN ISLAND OF ICE!" The next moment came the

dreadful crash! When I came to my senses from

the blow I received from being tossed from one

side of the forecastle to the other, I found

myself fast clinched with Palmer. The rest of the

watch had made their escape on deck, and shut

down the scuttle. After several unsuccessful

attempts to find the ladder to reach the scuttle,

we gave up in despair. We placed our arms

around each other's, necks, and gave up to die.

Amid the creaking and rending of the ship with

her grappled foe, we could once in a while hear

some of the screams and cries of some of our

wretched companions on the deck above us,

begging God for mercy, which only augmented

our desperate feelings. Thoughts came rushing

like the light that seemed to choke, and for a

few moments block up all way to utterance.

O, the dreadful thought! Here to yield up my

account and die, and sink with the wretched ship

to the bottom of the ocean, so far from home

and friends, without the least preparation, or

hope of heaven and eternal life, only to be

numbered with the damned and forever banished

from the presence of the Lord.

It seemed that something must give way to vent

my feelings of unutterable anguish!

In this agonizing moment the scuttle was thrown

open, with a cry, "Is there any one below?" In a

moment we were both on deck. I stood for a

moment surveying our position; the ship's bow

partly under a shelf of the ice, everything gone

but her stem. All her square sails filled with the

wind, and a heavy sea rushing her onward in

closer connection with her unyielding

antagonist. Without some immediate change it

was evident that our destiny, and hers, would be

sealed up in a few moments.

With some difficulty I made my way to the

quarter deck where the captain and second mate

were on their knees begging God for mercy. The

chief mate with as many as could rally around

him, were making fruitless efforts to hoist the

long boat, which could not have been kept from

dashing against the ice for two moments. Amid

the crash of matter and cry of others, my

attention was arrested by the captain's crying

out, "What are you going to do with me, Palmer?"

Said P, "I am going to heave you overboard!" "For

God's sake let me alone, said he, for we shall all

be in eternity in less than five minutes!" Said P.

with a dreadful oath, "I don't care for that, you

have been the cause of all this! It will be some

satisfaction to me to see you go first!" I laid fast

hold of him, and entreated him to let go of the

captain and go with roe and try the pump. He

readily yielded to my request; but to our utter

astonishment the pump sucked. This unexpected

good news arrested the attention of the chief

mate, who immediately turned from his fruitless

labor, and after a moment's survey of the ship's

crashing position, cried out with a stentorian

shout, "Let go the top gallant and the top-sail

halyards! Let go the tacks and sheets! Haul up

the courses! Clew down and clew up the

topsails!" Perhaps orders were never obeyed in

a more prompt and instantaneous manner. The wind thrown out of the sails relieved

the ship immediately, and like a lever sliding

from under a rock, she broke away from her

disastrous position, and settled down upon an

even keel broadside to the ice.

We now saw that our strong built and gallant

ship was a perfect wreck forward of her fore-

mast, and that mast, to all appearances, about

to go too; but what we most feared was, the

ship's yards and mast coming in contact with the

ice, in which case the heavy sea on her other

side would rush over her deck, and sink us in a

few moments. While anxiously waiting for this,

we saw that the sea which passed by our stern bounded against the western side of the ice, and

rushed back impetuously against the ship, and

thus prevented her coming in contact with the

ice, and also moved her onward towards the

southern extremity of the island which was so

high that we failed to see the top of it from the

mast head.

In this state of suspense we were unable to

devise any way for our escape, other than that

God in his providence was manifesting to us, as

above described. Praise his holy name! “His

ways are past finding out." About four o'clock in

the morning while all hands were intensely

engaged in clearing away the the wreck, a shout

was raised, "Yonder is the eastern horizon, and

it's daylight!" This was indication enough that

we were just passing from the western side,

beyond the southern extremity of the ice, where

the ship's course could be changed by human

skill.

"Hard up your helm," cried the captain, "and

keep the ship before the wind! Secure the fore-

mast! Clear away the wreck!" Suffice it to say

that fourteen days brought us safely into the

river Shannon, in Ireland, where we refitted for

our Russian voyage.

"They that go down to the sea in ships, that do

business in great waters: these see the works of

the Lord, aid his wonders in the deep. . . . Their

soul is melted because of trouble, . . . then they

cry unto the Lord in their trouble, and he

bringeth them out their distresses. . . . Oh, that

men would praise the Lord for his goodness, and

for his wonderful works to the children of men."

Psalms 107:8.

Dear young friends, whatever be your calling

here, "Seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his

righteousness,".

[Matthew 6:33,] and get your feet planted on

board the gospel ship. The owner of this

majestic homeward-bound vessel, shows the

utmost care for every mariner on board; even to

the numbering of the hairs of their heads. He not

only pays the highest wages, but has promised

every one who faithfully performs their duty an

exceeding great reward. That all the perils of

this voyage may be passed in safety, he has

commanded his holy ones [Hebrews 1:14] to

attend and watch over this precious company,

who fail not to flee through all the mist and

fogs, and give warning of all the dangers in the

pathway. Moreover he has invested his dear Son

with all power, and given him for a Commander

and skillful Pilot to convey this good ship and

her company into her destined haven. Then he

will clothe them with immortality, and give them

the earth made new for an everlasting

inheritance; and make them kings and priests

unto God, to "reign on the earth."

Eaton Rapids, Michigan

JOSEPH BATES.

INCIDENTS OF MY PAST LIFE. No. 4.

PARTING THE CABLE TAKEN BY PRIVATEERS

LITTLE BOX SHIP CONDEMNED.

AFTER repairing damages in Ireland we sailed

again on our Russian voyage, and in a few

days we fell in with & joined an English convoy

of two or three hundred sail of merchant vessels

bound into the Baltic sea, convoyed by British

ships of war to protect them from their enemies.

On reaching a difficult place called the "Mooner

passage," a violent gale overtook us which in

spite of our efforts was driving us on a dismal,

shelterless shore. With the increasing fury of the

gale and darkness of the night, our condition

became more and more alarming, until finally our

Commodore hoisted the "lighted lantern." a

signal for all the fleet to anchor without delay.

The long wished for morning at length came

which revealed to us our alarming position. All

that were provided with cables were contending

with the boisterous seas driven against us by

the furious gale. It seemed almost a miracle to

us that our cables and anchors still held. While

watching one after another as they parted their

cables and were drifting towards the rocks to

be dashed in pieces, our own cable broke!

With all haste we crowded what sail we dared on

the ship, and she being a fast sailor we found by

the next day that we had gained some distance

in the offing. Here a council was called which

decided that we should make sail from the

convoy and take a lone chance through the

sound, by the coast of Denmark.

Not many hours from this, while we were

congratulating ourselves respecting our narrow

escape from shipwreck, and out of reach of the

Commodore's guns, two suspicious looking

vessels were endeavoring to cut us off from the

shore. Their cannon balls soon began to fall

around us. And it became advisable for us to

round too and let them come aboard. They

proved to be two Danish privateers, who

captured and took us to Copenhagen, where

ship and cargo were finally condemned, in

accordance with Bonaparte's decrees, because

of our intercourse with the English.

In the course of a few weeks we were all called

to the court house to give testimony respecting

our voyage. Previous to this, our supercargo and

part owner had promised us a handsome reward

if we would testify that our voyage was direct

from New York to Copenhagen, and that we had

no intercourse with the English. To this

proposition we were not all agreed. We were

finally examined! separately, my turn coming

first. I suppose they first called me into court

because I was the only youth among the sailors.

One of the three judges asked me in English if I

understood the nature of an oath. After

answering in the affirmative he bid me look at

a box near by, (about 15 inches long and 8 high.)

and said, that box contains a machine to cut off

the two fore-fingers and thumb of every one who

swears falsely here. Now, said he, hold up your

two fore-fingers & thumb on your right hand. In

this manner I was sworn to tell the truth, and

regardless of any consideration I testified to the

facts concerning our voyage.

Afterwards when we were permitted to go

aboard it was clear enough that the "little box"

had brought out the truthful testimony from all;

viz., that we had been wrecked by running

against an island of ice fourteen days from New

York; refitted in Ireland, after which we joined

the British convoy, and were captured by the

privateers. After this, some of our crew as they

were returning from a walk where they had been

viewing the prison, said that some of the

prisoners thrust their hands through the gratings

to show them that they had lost the two fore-

fingers and thumb of their right hand. They were

a crew of Dutchmen that were likewise taken

and had sworn falsely. We now felt thankful for

another narrow escape by telling the truth.

" We want the truth on every point,

We want it too, to practice by."

With the condemnation of our ship and cargo,

and loss of our wages, in company with a

strange people who had stripped us of all but our

clothing, ended our Russian voyage. But before

Winter set in I obtained a birth on board a

Danish brig bound to Pillau, in Prussia, where we

arrived after a tedious passage, our vessel

leaking so badly that it was with difficulty we

kept her from sinking until we reached the

wharf. In this extremity I obtained a berth on an

American brig from Russia, bound to Belfast,

Ireland. But I must close now.

Dear Youth: By reading the foregoing sketch

you will at once see how soon troubles came

after our cable parted from the anchor. This will

illustrate the perilous condition of those who

while on the voyage of life" to the port of eternal

rest, suffer their cable to part from the heavenly

anchor.

This cable is faith, End the anchor to which it is

secured is hope. As the strength of the mariner's

cable is tried by storms and tempests, so the

Christian's cable, (faith.) is proved by the various

trials and commotions of life. Therefore we

should watch and pray and be sure that our

cable is firmly fastened to the blessed hope,

which we have as an anchor of the soul both

SURE and STEADFAST."

JOSEPH BATES.

Leslie, Michigan

INCIDENTS OF MY YOUTH. No. 5.

VOYAGE TO IRELAND IMPRESSED INTO THE

BRITISH SERVICE ATTEMPT TO

ESCAPE IMPRISONMENT.

OUR voyage from Prussia to Ireland was replete

with trials and suffering. It was a Winter passage

down the Baltic Sea. And through the winding

passages of the High lands of Scotland, under

a cruel, drunken, parsimonious captain, who

denied us enough of the most common food

allowed to sailors. And when through his

neglect to furnish such, we were in a famishing

condition and almost exhausted with pumping to

keep us from sinking, he would swear and

threaten us with severer usage if we failed to

comply with his wishes. Finally after putting

into an Island and furnishing a fresh supply of

provisions, we sailed again for Belfast, in

Ireland, where the voyage ended. From thence

two of us crossed the Irish Channel to Liverpool,

to seek a voyage to America. A few days after

our arrival ''a press-gang" (an officer and twelve

men) entered our boarding house in the evening

and asked to what country we belonged. We

produced our American protections which proved

us to be citizens of the United States.

Protections and arguments would not satisfy

them. They seized and dragged us to the

"rendezvous," a place of close confinement. In

the morning we were examined before a naval

Lieutenant, and ordered to join the British Navy.

To prevent our escape, four stout men seized

us, and the Lieutenant with his drawn sword

going before we were conducted through the

middle of one of the principal streets of

Liverpool like condemned criminals ordered to

the gallows. When we reached the river side,

a boat well manned with men was in readiness,

and conveyed us on board the Princess, of the

Royal Navy. Here we were measured, and a

minute description of our persons taken and then

confined in the prison room on the lower deck,

with about sixty others who claimed to be

Americans, and impressed in like manner as

ourselves. This eventful epoch occurred April

27th, 1810.

One feeling seemed to pervade the minds of all

who claimed to be Americans; viz., that we were

unlawfully seized, without any provocation on

our part, hence any way by which we could

regain our liberty would be justifiable. In a few

days the greater portion of the officers and crew

took one of their dead on shore to be buried. It

was then suggested by some that this was a

favorable time for us to brake the iron bars and

bolts in the porthole and make our escape by

swimming in the strong current that was

rushing by us. In breaking the bars we

succeeded beyond our expectation, and when all

ready to cast ourselves overboard, one after

another, the boats came along side with the

officers, and our open place was discovered.

For this they began by taking one after another

and whipping them on their naked backs in a

most inhuman-manner. This dreadful work was in

progress for several hours, and closed about

nine o'clock at night, intending to finish next

day. But they did not have time to carry out their

cruel work, for orders were given to trans-ship

us all on board a Frigate near by, that was

weighing her anchors to put to sea. In a few days

we came to Plymouth, where we were

reexamined, and all such as were pronounced

in good condition for service in the British Navy

were transferred to one of their largest sized

stationary ships, called the “Saint Salvador Del

Hondo." On this monstrous floating castle were

fifteen hundred persons in the same condition

as myself.

Here, in conversation with a young man from

Massachusetts, we agreed to try to make our

escape if we perished in the attempt. We

prepared us a rope and closely watched the

soldiers and sailors on guard till they were being

relieved from their posts at midnight. We then

raised the ''hanging port" about eighteen inches,

and put the "tackle fall" in the hands of a friend

in the secret, to lower it down when we were

beyond the reach of the musket balls. Our rope

and blanket, about thirty feet long, reached the

water. Forbes, my companion, whispered,

“Will you follow?" I replied,

"Yes." By the time he reached the water

I was slipping down after him, when the alarm

ran through the ship,. "A man overboard." Our

friend dropt the "port" for fear of being detected,

which left me exposed to the fire of the

sentinels.

But I was soon in the water, and swam to a

hiding place under the "accommodation ladder"

by the time the boats were manned, with

lanterns, to hunt us out. We watched for an

opportunity to take an opposite direction from

our pursuers, who were repeatedly hailed from

the ship to know if they had found any one. We

had about three miles to swim with our clothes

on except our jacket and shoes;

these I had fastened on the back of my neck to

screen me from a chance shot from the ship. An

officer with men and lanterns descended the

"accommodation ladder," and sliding his hand

over the "slat" he touched my hand, and

immediately shouted, "Here is one of them! Come

out of that, you sir! Here is another! Come out,

you sir!"

We swam round to them and were drawn upon

the stage, "Who are you?" demanded the officer.

"An American." "How dare you undertake to

swim away from the ship? Did you not know

that you were liable to be shot?" I answered that

I was not a subject of King George, and had done

this to gain my liberty. ''Bring them up here!"

was the order from the ship. After another

examination we were put into close confinement

with a number of criminals awaiting their

punishment.

DEAR YOUNG FRIENDS; I never fully realized the

oppressive nature of bondage nor the value of

freedom before. Since that time God in great

mercy enabled me to see that I was in willing

bondage to the most cruel tyrant that ever lived,

and that there was but one way to escape his

power, and that by believing on the name of the

only begotten Son of God. My prayer also is that

no consideration may prevent

you from fleeing from the murderous power of

the Devil, [John 8:44,] and by faith laying hold of

the Son of the living God for freedom. "For if the

Son makes you free, then are you free indeed."

Blackman, Michigan

JOSEPH BATES.

INCIDENTS Of MY PAST LIFE. No, 6.

Introduction into the British service Spanish war

ships —A Leranter Image worship—Another attempt

for freedom—Battle— Storm—Spanish -war ship wrecked—

Blockading squadron—Church service on board a

king's ship.

AFTER some thirty hour's of close confinement

I was separated from my friend and hurried

away with about one hundred and fifty sailors

(all strangers to me) to join his Majesty's ship

"Rodney," of 74 guns, whose crew numbered

about seven hundred men. As soon as we had

passed our muster on the quarter deck of the

Rodney, all were permitted to go below and get

their dinners but Bates,— Commander Bolton

handed the First Lieutenant a paper, on reading

of which he looked at me and muttered,"

scoundrel." All the boats' crews amounting to

more than, one hundred men were immediately

assembled on the quarter deck. Said Capt.

Bolton, "Do you see that fellow?" "Yes sir." " If

ever you allow him to get into one of your boats,

I will flog every one of the boat's crew." " Do

you understand me?”

"Yes sir, yes sir." was the reply. "Then go

down to your dinners, and you may go too, sir."

I now began to learn something of the nature

of my punishment for attempting in a quiet and

peaceable manner to quit his majesty's service.

In the commanding officer's view this seemed to

amount to an unpardonable crime, and never to

be forgotten. In a few hours the Rodney under a

cloud of sail, was leaving Old Plymouth in the

distance, steering for the French coast to make

war with Frenchmen. "Hope deferred makes the

heart sick;" thus my hope of freedom from this

oppressive state, seemed to wane from my view

like the land we were leaving in the distance.

As our final destination was to join the British

squadron in the Gulf of Lyons, in the

Mediterranean sea, we made a stop at Cadiz in

Spain. Here the French troops of Napoleon

Bonaparte were bombarding the city, and British

and Spanish ships of war in the harbor. These

comprised a part of the Spanish fleet that finally

escaped from the battle of Trafalgar, under Lord

Nelson in 1805, and were now to be refitted by

their ally the English, and sail for Port Mahon in

the Mediterranean. Unexpectedly I was one of

fifty selected to refit and man one of them, the

''Apollo." A few days after passing the straits of

Gibraltar we encountered a most violent gale of

wind, called a "Levanter," common in those

seas, which caused our ship to labor so

excessively that it was with the utmost

exertions at the pumps that we kept her from

sinking.

We were finally favored to return back to

Gibraltar and refit.

A number of Spanish officers with their

families still belonged to the ship. It was

wonderful and strange to us to see how

tenaciously this people hung around their

images, surrounded with burning wax candles,

as though they could save them in this perilous

hour, when nothing short of our continual labor

at the pumps, prevented the ship from sinking

with us all.

After refitting at Gibraltar, we sailed again

and arrived safely at the Island of Mahon. Here I

made another attempt to regain my liberty with

two others, by inducing a native to take us to

land in his market boat. After some two days and

nights of fruitless labor to escape from the

Island by boats or otherwise, or from those who

were well paid for apprehending deserters, we

deemed it best to venture back. Our voluntary

return to the ship was finally accepted as

evidence that we did not design to desert from

the service of King George III. Thus we

escaped from being publicly whipped.

Our crew was now taken back to Gibraltar to

join the Rodney, our own ship, who had just

arrived in charge of another Spanish line of

battle ship for Port Mahon, having a crew of fifty

of the Rodney's men. In company with our

Spanish consort we sailed some eighty miles on

the way to Malaga, where we discovered the

combined armies of the English and Spanish in

close engagement with the French army on the

seaboard. Our ship was soon moored broad side

to the shore. As the orders for furling the sails

were not promptly obeyed by reason of the

Frenchmen's shot from the fort, all hands were

ordered aloft, and there remained exposed to

the enemy's shot until the sails were furled. This

was done out of anger. While in this condition a

single well directed shot might have killed a

score, but fortunately none were shot till all had

reached the deck, Our thirty two pound balls

made dreadful havoc for a little while with the

enemy's ranks: nevertheless they soon managed

to bring their enemies between us and thereby

check our firing. Then with a furious onset they

drove them to their fortress, and many seeing

our boats near the shore, rushed into the sea

and were either shot by the French or drowned,

except what the boats floated to our ship, This

work commenced about 2 P. M., and closed with

the setting sun. After disposing of the dead and

washing their blood from the decks, we sailed

away with our Spanish consort for Port Mahon.

Just before reaching there, another "Levanter"

came on so suddenly that it was with much

difficulty that we could manage our new built

ship. Oar Spanish consort unprepared for such a

violent gale, was dashed to pieces on the rocks

on the Island of Sardinia, and most every one of

the crew perished. After the gale we joined the

British fleet consisting of about thirty line of

battle ships, carrying from eighty to one hundred

and thirty guns apiece, besides frigates and

sloops of war, Our work was to blockade a much

larger fleet of French men of war, mostly in the

harbor of Toulon.

With these we occasionally had skirmishes or

running fights.

They were not prepared, neither disposed to

meet the English in battle.

To improve oar mental faculties when we had

a few leisure moments from ship duty and naval

tactics, we were furnished with a library of two

choice books for every ten men (We had seventy

of these libraries in all.)

The first book was an abridgement of the life

of Lord Nelson, calculated to inspire the mind

with deeds of valor, and the most summary way

of disposing of an unyielding enemy. This, one of

the ten men could read, when he had leisure,

during the last six days or each week. The

second was a small Church of England prayer

book, for special use, about one hour on the first day of the week.

CHURCH SERVICE ON BOABD A KING'S SHIP.

As a general thing a chaplain was allowed for

every large ship.

When the weather was pleasant the quarter deck

was fitted with awnings, flags, benches, &c. for

meeting At 11 A. M., came the order from the

officer of the deck,

"Strike six bells there!"

''Yes sir." " Boatswain's mate?"

''Sir." "Call all hands to church! Hurry them up

there!" (These mates were required to carry a

piece of rope in their pocket to start sailors

with) Immediately their stentorian voices were

heard sounding on the other decks, "Away up to

church there every soul of you and take your

prayer books with you!"

If any one felt disinclined to such a mode of

worship, and attempted to evade the loud call to

church, then look out for the men with the rope!

When I was asked." Of what religion are you?"

I replied, "A Presbyterian."

But I was now given to understand that there

was no religious toleration on board the king's

war ships." Only one denomination here away

with you to church!" The officers before taking

their seats unbuckled their swords and dirks

and piled them on the head of the capstan, in the

midst of the worshipping assembly, all ready to

grasp them in a moment if necessary before the

hour's service should close. When the

benediction was pronounced, the officers

clinched their side arms, and buckled them on

for active service. The quarter deck was

immediately cleared, and the floating Bethel

again becomes the same old weekly war ship for

six days and twenty-three hour's more.

Respecting the church service, the chaplain,

or in his absence, the Captain reads from the

prayer book, and the officers and sailors

respond. And when he read about the Law of

God, the loud response would fill the quarter

deck, "0 Lord, incline our hearts to keep thy

Law."

Poor wicked, deluded souls! How little their

hearts were inclined to keep the holy Law of

God, when almost every other hour of the week

their tongues were employed in blaspheming his

holy name; and at the same time learning and

practicing the way and manner of shooting,

slaying, and sinking to the bottom of the ocean

all that refused to surrender and become their

prisoners; or who dared to oppose or array

themselves in opposition to a proclamation of

war issued from their good old Christian king.

King George III not only assumed the right to

impress American seaman to man his war ships,

and fight his unjust battles, but he also required

them to attend his church and learn to respond

to his preachers. And whenever the band of

musicians on ship board commenced with "God

save the king!" they, with all his loyal subjects

were also required to take off their hats in

obeisance to his royal authority.

At that time I felt a wicked spirit towards

those who deprived me of my liberty, and held

me in this state of oppression, and required me

in their way to serve God, and honor their king

But I thank God who teaches us to forgive and

love our enemies; that through his rich mercy in

Jesus Christ I have since found forgiveness of

my sins; that all such feelings are subdued, and

my only wish is that I could teach them the way

of life and salvation.

JOSEPH BATES.

Battle Creek, Michigan,

INCIDENTS OF MY PAST LIFE;. No. 7

Port Mahon—Subterranean passage Holy

stone—Wash day—Threatened punishment—

Trying hour—-Dreadful storm——Twenty-four

hours' liberty—New situation.

THE winter rendezvous of the Mediterranean

British squadron was in the isle of Minorca,

harbor of Port Mahon. Sailing after the middle of

the seventh month is dangerous. See St. Paul's

testimony, Acts 27:9,10. While endeavoring to

escape the vigilance of our pursuers, after we

stepped out of the Spaniard's market boat (see

No. 6,) away beyond the city, at the base of a

rocky mountain we discovered a wooden door

which we opened, and away in the distance it

appeared quite light. We ventured on through

this subterranean passage till we came to a

large open space where the light was shining

down through a small hole wrought from the top

of the mountain, down through the dome. This

subterranean passage continued on in a winding

direction which we attempted to explore as far

as we dared to for the want of light to return to

the center. On both sides of this-main road we

discovered similar passages all beyond our

exploration. Afterwards we were told that this

mountain had been excavated in past ages for

the purpose of sheltering a besieged army. In the

center or light place was a large house chiseled

out of a rock, with door way and window frames,

designed undoubtedly for the officers

of the besieged, and rallying place of the army.

After a close survey of this wonderful place, we

became satisfied that we had now found a

secure retreat from our pursuers, where we

could breathe and talk aloud without fear of

being heard, or seized by any of the subjects of

King George III.

But alas, our joy soon vanished when we thought

again that there was nothing here to eat. When

we ventured to a farm house to seek for

bread, the people eyed us with suspicion, and

fearing they would seize us, and hand us over to

our pursuers, we avoided them, until we became

satisfied that it was in vain to escape from this

place and so returned to the ship. The stone of

this mountain is a kind of sand-stone, much

harder than chalk, called “holy stone" which is

abundant on the island, and made use of by the

British squadron to scour or holy-stone the

decks with every morning, to make them white

and clean. In the mild seasons, the sailor's

uniform was white duck frocks and trousers, and

straw hats. The discipline was, to muster all

hands at nine o'clock in the morning, and if our

dress was reported soiled or unclean, then all

such were doomed to have their names put on

the ''black list," and required to do all kinds of

scouring brass, iron and filthy work, in addition

to their stationed duty, depriving them of their

allotted time for rest and sleep in their morning

watch below. There was no punishment more

dreaded and disgraceful to which we were daily

liable.

If sufficient changes of dress had been allowed

us, and sufficient time to wash and dry the same,

it would have been a great pleasure, and also a

benefit to us to have appeared daily with

unsoiled white dresses on, notwithstanding the

dirty work we had to perform. I do not remember

of ever being allowed more than three suits at

one time to make changes, and then only one

day in the week to cleanse them, viz. about two

hours before daylight once a week, all hands

(about 700) called on the upper decks to wash

and scrub clothes.

Not more than three quarters of these could be

accommodated to do this work for themselves

at a time; but no matter, when daylight came at

the expiration of the two hours, all washed

clothes were ordered to be hung on the clothes-

lines immediately.

Some would say, I have not been able to

get water nor a place to wash mine yet. "I can't

help that! Clear out your clothes, and begin to

holy-stone and wash the decks." Orders were

most strict that whoever should be found drying

his clothes at any other but this time in the wash

day should be punished. To avoid detection and

punishment, I have scrubbed my trousers early

in the morning, and put them on and dried them.

Not liking this method, I ventured at one time to

hang up my wet trousers in a concealed place

behind the main top sail; but the sail was

ordered to be furled in a hurry, and the

lieutenant discovered them. The maintop men

(about fifty) were immediately ordered from

their dinner hour to appear on the quarter deck.

"All here Sir," said the under officer that

mustered us. "Very well, whose trousers are

these found hanging in the maintop?"

I stepped forward from the ranks, and said,

''They are mine, Sir." "Yours, are they? You!"

and when he had finished cursing me he asked

me, how they came there? "I hung them there to

dry, Sir." "You see how I will hang you, directly.

Go down to your dinner, the rest of you." said

he, "and call the chief boatswain's mate up

here." Up he came in great haste from his dinner.

"Have you got a rope's end in your pocket?" He

began to feel and said, "No Sir."

"Then away down below directly and get one and

give that fellow there one of the floggings he

ever had." "Yes, Sir, bare a hand."

Thus far, I had escaped all his threats of

punishment from my first introduction into the

ship.

I had often applied for more clothes to enable me

to muster with a clean dress, but had been

refused.

I expected now, according to his threats, that he

would wreak his vengeance on me by having the

flesh cut off my back for attempting to have a

clean dress, when he knew I could not have it

without venturing some way as I had done. While

thoughts of the unjustness of this matter were

rapidly passing through my mind, he cried out,

"Where is that fellow with the rope? Why don't

he hurry up here? " At this instant he was heard

rushing up from below. The lieutenant stopped

short and turned to me saying. "If you don't want

one of the floggings you ever had, do you

run." I looked at him to see if he was in earnest.

The under officer, who seemed to feel the

injustice of my case, repeated, "Run!" The

lieutenant cried to the man with the rope, "Give

it to him!"

''Aye, aye, Sir." I bounded forward, and by the

time he reached the head of the ship, I was over

the bow getting a position to receive him near

down by the water, on the ship's bobstays. He

saw at a glance it would require his utmost skill

to perform his pleasing task there. He therefore

commanded me to come up to him. "No," said I,

"if you want me, come here."

In this position, the Devil, the enemy of all right

and just motives, tempted me to seek a summary

redress of my grievances, viz. if he followed me

and persisted in inflicting on me the threatened

punishment, to grasp him and plunge into the water.

Of the many that stood above looking on.

none spake to me that I remember but my

pursuer. To the best of my memory I remained in

this position more than an hour. To the wonder

of myself and others, the lieutenant issued no

me, neither questioned me afterwards, only the

next morning I learned that I was numbered with

the black list men for about six months.

Thanks to the Father of all mercies for delivering

me from premeditated destruction by his

overruling providence in that trying hour.

Ships belonging to the blockading squadron in

the Mediterranean sea were generally relieved

and returned to England at the expiration of

three years; then the sailors were paid their

wages, and twenty-four hours' liberty given them

to spend their money on shore. As the Rodney

was NOW on her third year out, my strong hope

of freedom from the British yoke would often

cheer me while looking forward to that one day's

liberty in the which I was resolving to put forth

every energy of my being to gain my freedom.

About this time the fleet encountered a most dreadful storm in the gulf of Lyons. For a while it

was doubted whether any of us would ever see

the rising of another sun. These huge ships

would rise like mountains on the top of the

coming sea, and suddenly tumble again into the

trough of the same with such a dreadful

crash that it seemed almost impossible they

could ever rise again. They became

unmanageable, and the mariners were at their

wit's end. See the Psalmist's description. Psalms

197:23-30. On our arrival at Port Mahon in the

island of Minorca, ten ships were reported much

damaged.

The Rodney was so badly damaged that the

commander was ordered to get her ready to

proceed to England. Joyful sound to us all!

"Homeward bound! Twenty-four hour's liberty!"

was the joyous sound. All hearts glad. One

evening after dark, just before the Rodney's

departure for England, some fifty of us were

called out by name and ordered to get our

baggage ready and get into the boats. "What's

the matter? Where are we going?" "On board the

Swiftshore 74." ' What, that ship that has just

arrived for a three year's station?" "Yes.”: A sad

disappointment indeed; but what was still

worse, I began to learn that I was doomed to

drag out a miserable existence in the British

navy. Once more I was among strangers, but well

known as one who had attempted to escape

from the service of King George III.

-The Swiftshore was soon under way for her

station off Toulon. A few days after we sailed, a

friend of try father's arrived from the United

States bringing documents to prove my

citizenship and a demand for my release from

the British Government.

JOSEPH BATES.

Springport, Michigan

June 14, 1859.

INCIDENTS IN MY PAST LIFE. No. 8.

Impressing American seaman — Documents of

citizenship

— Declaration of war — Voluntary surrender as

prisoners

of war — Preparation for a battle on the ocean

— Unjust treatment — Close confinement.

ONE of the most prominent causes of our last

war of 1812 with England was her oppressive

and unjust acts in impressing American seaman

on sea or land, wherever they could be found.

This was denied by one political party in the

United States. The British government also

continued to deny the fact, and the regard of

American citizens was of but little importance.

Such proof of American citizenship as was

required by them was not very readily obtained.

Hence their continued acts of aggression until

the war.

Another additional and grievous act was that all

letters to our friends were required to be

examined by the first lieutenant before leaving

the ship. By accident I found one of mine torn

and thrown aside, hence the impossibility of my

parents learning even that I was among the

living. With as genuine a protection as could be

obtained from the collector of the custom house

at N. Y. city, I nevertheless was passed off for

an Irishman, because an Irish officer declared

that my parents lived in Belfast, Ireland.

Previous to the war of 1812 one of my letters

reached my father. He then procured for me

another protection from the collector of the port

of New Bedford, Mass., who had known me from

childhood.

He also wrote to the president of the United

States (Madison) presenting him with the facts

in my case, and for proof of his own citizenship

referred him to the archives in the war

department for his commissions returned and

deposited thereafter his services closed with the

Revolutionary war.

The president's reply and documents were

satisfactory. Gen. Brooks, then Gov. of Mass.,

who was intimately acquainted with my father

as a captain under his immediate command in

the Revolutionary war, added to the foregoing

another strong document, all of which were

afterwards critically reviewed in England and

sent out in pamphlet form. Subsequently, during

my imprisonment there, it was placed in my

hands.

Capt. C. Delano, townsman and friend of my

father, preparing for a voyage to Minorca, in the

Mediterranean, generously offered his services

to be bearer of the above named documents,

and so sanguine was he that no other proof

would be required that he really expected to

bring me with him on his return voyage.

On his arrival at port*Mahon, he was rejoiced to

learn that the Rodney, 74, was in port. As he

approached the R. in his boat, he was asked

what he wanted. He said he wished to see a

young man by the name of Joseph Bates. The

lieutenant forbid his coming alongside. Finally

one of the under officers, a friend of mine,

informed him that I had been transferred to the

Swiftshore, 74, (see No. 7,) and she had sailed

to join the British fleet off Toulon. Capt. D. then

presented my documents to the United

States Consul, who transmitted them to Sir

Edward Pelew, the commander-in-chief of the

squadron.

On the arrival of the mail, I received a letter from

Capt. D. informing me of his arrival, and visit to

the R., his disappointment, and what he had

done, and of the anxiety of my parents. I think

this was the first intelligence from home for over

three years.

I was told that the Capt. had sent for me to see

him on the quarter deck. I saw he was

surrounded by signal men and officers replying

by signal flags to the admiral's ship which was

some distance from us. Said the Capt., Is your

name Joseph Bates? Yes sir.

Are you an American? Yes sir. To what part of

America do you belong? New Bedford, in Mass.,

sir. Said he, the admiral is inquiring to know if

you are on board this ship. He will probably send

for you, or something to the like import. You may

go below. The news spread throughout the ship

that that Bates was an American, and his

government had demanded his release, and the

commander-in-chief was signalizing our ship

about it, &c. What a lucky fellow he was, &c.

Weeks and months rolled away, however, and

nothing but anxious suspense and uncertainty in

my case, till at length I received another letter

from Capt. D. informing me my case was still

hanging in uncertainty, and it was probable war

had commenced and he was obliged to leave,

and if I could not obtain an honorable discharge,

I had better become a prisoner of war.

It was now the fall of 1812. On our arrival at

port Mahon to winter, the British consul sent me

what money I then needed, saying that it was

Capt. D.'s request that he should furnish me with

money and clothing while I needed. Owing to

sickness in the fleet, it was ordered that each

ship's company should have 24 hours liberty on

shore. I improved this opportunity to call at the

offices of the British and American consuls. The

former furnished me with some more money. The

latter said that the admiral had done nothing in

my case, and now it was too late, for it was

ascertained that war was declared

between the United States and Great Britain.

There were about two hundred Americans on

board the ships in our squadron, and 22 on board

the Swiftshore. We had ventured several times to

say what we ought to do, but the result appeared

to some very doubtful. At last some six of us

united and walked to the quarter deck with our

hats in hand, and thus addressed the first

lieutenant: we understand, sir, that war has

commenced between Great Britain and the

United States, and we do not wish to be found

fighting against our own country;

therefore it is our wish to become prisoners of

war.

“Go below.” At dinner hour all the Americans

were ordered between the pumps, and not

permitted to associate with the crew. Our scanty

allowance was ordered to be reduced one third,

and no strong drink. This we felt we could

endure, and not a little comforted that we had

made one effectual change, and the next would

most likely free us from the British yoke.

From our ship the work spread until about all

the Americans in the fleet became prisoners of

war.

During eight dreary months we were thus

retained and frequently called upon the quarter

deck and harangued and urged to enter the

British navy. I had already suffered on for thirty

months an unwilling subject. I was therefore

fully decided not to listen to any proposal they

could make.

A few months after our becoming prisoners of

war, our lookout ships appeared off the harbor,

and signalized that the French fleet (which we

were attempting to blockade) were all out and

making the best of their way down the

Mediterranean. With this startling information

orders were immediately issued for all the

squadron to be ready to proceed in pursuit of

them at an early hour in the morning.

The most of the night was spent preparing for

this expected onset. The prisoners were invited

to assist.

I alone refused to aid or assist in any way

whatever, it being unjustifiable except when

forced to do so. In the morning the whole fleet

was sailing out of the harbor in line of battle.

Gunners were ordered to double-shot the guns,

and clear away for action. The first lieutenant

was passing by where I stood reading the life of

Nelson. (One of the library books.) Take up that

hammock, sir, and carry it on deck. I looked off

from the book and said it's not mine, sir. Take it

up. It's not mine, sir. He cursed me for a

scoundrel, snatched the book from me, and

dashed it out of the gun port, and struck me

down with his fist. As soon as I got up, said he,

Take that hammock (some one's bed and

blankets lashed up) on deck. I shall not do it,

sir! I am a prisoner of war, and hope you

will treat me as such. Yes, you Yankee

scoundrel, I will. Here, said he to two under

officers, take that hammock and lash it on to

that fellow's back, and make him walk the poop

deck 24 hours with it. And because I put my

hands on them to keep them from doing so, and

requested them to let me alone, he became

outrageous, and cried out, Blaster at arms! Take

this fellow into the gun-room and put him double

legs in irons! That you can do, sir, said I, but I

shall not work. When we come into action I'll

have you lashed up in the main rigging

for a target, for the Frenchmen to fire at!

That you can do, sir, but I hope you will

remember that I am a prisoner of war. Another

volley of oaths and imprecations followed, with

an inquiry why the master-at-arms did not hurry

up with the irons.

The poor old man was so dismayed and galled

that he could not find them. He changed his

mind, and ordered him to come up and make me

a close prisoner in the gun room, and not allow

me to come near any one, nor even to speak with

one of my countrymen.

With this he hurried up on the upper gun

deck where orders were given to throw all the

hammocks and bags into the ship's hold, break

down all cabin and berth partitions, break up

and throw overboard all the cow and sheep pens,

and clear the deck fore and aft for action. Every

ship was now in its station for battle, rushing

across the Mediterranean for the Turkish shore,

watching to see and grapple with their deadly

foe.

JOSEPH BATES.

Monterey, July 18th, 1859.

INCIDENTS IN MY PAST LIFE. NO. 9.

Release from close confinement—British fleet out-

generaled—

Removed to a prison-ship in England—Provisions

for a London newspaper—General excitement

in relation to our bread—Another movement.

WHEN all the preparation was made for battle,

one of my countrymen, in the absence of the

master of arms, ventured to speak with me

through the musket gratings of the gun-room,

to warn me of the perilous position I should be

placed in when the French fleet hove in sight

unless I submitted, and acknowledged myself

ready to take my former station [second captain

of one of the big guns on the forecastle] and

fight the Frenchmen, as he and the rest of my

countrymen, were about to do. I endeavored

to show him how unjustifiable and inconsistent

such a course would be for us as prisoners of

war, and assured him that my mind was fully and

clearly settled to adhere to our position as

American prisoners of war, notwithstanding the

perilous position I was to be placed in.

In the course of a few hours, after the lieutenant

had finished his arrangements for a battle, he

came down into my prison-room. Well sir, said

he, will you take up a hammock when you are

ordered again? I replied that I would take one up

for any gentleman in the ship. You would, ha!

Yes sir: without inquiring who I considered

gentlemen, he ordered me released. My

countrymen were somewhat surprised to see

me so soon a prisoner at large.

The first lieutenant is next in command to the

captain, and presides over all the duties of the

ship during the day, and keeps no watch,

whereas all other officers do. As we had not yet

seen the French fleet, the first lieutenant was

aware that my case would have to be reported

to the captain; in which case if I, as an

acknowledged prisoner of war, belonging to the

United States, was allowed to answer for

myself, his unlawful, abusive, and ungentlemanly

conduct would come to the captain's knowledge.

Hence his willingness to release me.

The British fleet continued their course across

the Mediterranean for the Turkish coast until

they were satisfied that the French fleet was

not to the west of them. They then steered

north and east (to meet them) until we arrived

off the harbor of Toulon, where we saw them all

snugly moored, and dismantled in their old

winter quarters; their officers and crews

undoubtedly highly gratified that the ruse they

had practiced had so well effected their design,

viz., to start the British squadron out of their

snug winter quarters to hunt for them over the

Mediterranean sea. They had remantled, and

sailed out of their harbor, and chased our few

lookout ships a distance down the Mediterranean

and when unperceived by them returned and

dismantled again.

After retaining us prisoners of war about eight

months, we with others that continued to refuse

all solicitation to rejoin the British service,

were sent to Gibralter, and from thence to

England, and finally locked up on board an old

sheer-hulk, called the crown Princen, formerly a

Danish 74 gun ship, a few miles below Chatham

dock-yard, and seventy miles from London. Here

were many others of like description, many of

them containing prisoners.

Here about seven hundred prisoners were

crowded between two decks, and locked up

every night, on a scanty allowance of food, and

in crowded quarters.

Cut off from all intercourse except floating news,

a plan was devised to obtain a newspaper, which

often relieved us in our anxious, desponding

moments, although we had to feel the pressing

claims of hunger for it. The plan was this: One

day in each week we were allowed salt fish; this

we sold to the contractor for cash, and paid out

to one of our enemies to smuggle us in one of

the weekly journals from London. This being

common stock, good readers were chosen to

stand in an elevated position and read aloud. It

was often interesting and amusing to see the

perfect rush to hear every word of American

news, several voices crying out, "Read that over

again, we could not hear it distinctly;" and the

same from another, and another quarter.

Good news from home often cheered us

more than our scanty allowance of food. If more

means had been required for the paper, I believe

another portion of our daily allowance would

have been freely offered, rather than give it up.

Our daily allowance of bread consisted of coarse

brown loaves from the bakery, served out every

morning. At the commencement of the severe

cold weather, a quantity of ship biscuit was

deposited on board for our use in case the

weather or ice should prevent the soft bread

from coming daily.

In the spring, our first lieutenant, or commander,

ordered the biscuit to be served out to the

prisoners, and directed that one quarter of the

daily allowance should be deducted, because

nine ounces of biscuit were equal to twelve

ounces of soft bread. We utterly refused to

receive the biscuit, or hard bread,

unless he would allow us as many ounces as we

had had of the soft. At the close of the day he

wished to know again if we would receive the

bread on his terms. No! No! Then I will keep you

below until you comply. Hatchways unlocked in

the morning again. Will you come up for your

bread? No.

At noon again, Will you have your meat that is

cooked for you? No! Will you come up for your

water? No, we will have nothing from you until

you serve us out our full allowance of bread. To

make us comply, the port holes had been closed,

thus depriving us of light and fresh air. Our

president also had been called up and conferred

with, [we had a president, and committee of

twelve chosen, as we found it necessary to

keep some kind of order]. He told the commander

that the prisoners would not yield.

By this time hunger and the want of water, and

especially fresh air, had thrown us into a state of

feverish excitement. Some appeared almost

savage, others endeavored to bear it as well as

they could.

The president was called for again. After awhile

the port where he messed was thrown open, and

two officers from the hatchway came down on

the lower deck and passed to his table, enquiring

for the president's trunk. What do you want with

it?

said his friends. The commander has sent us for

it. What for? He is going to send him on board

the next prison ship. Do you drop it! He shall

not have it! By this time the officers became

alarmed for their safety, and attempted to make

their escape up the ladder, to the hatchway. A

number of the prisoners who seemed fired with

desperation, stopped them, and declared on the

peril of their lives that they should go no further

until the president was permitted to come down.

Other port holes were now thrown open, and the

commander appeared at one of them, demanding

the release of his officers. The reply from within

was, When you release our president we will

release your officers. If you do not release them,

said the commander, I will open these ports (all

of them grated with heavy bars of iron) and fire

in upon you. Fire away! Was the cry from within,

we may as well die this way as by famine; but

mark, if you kill one prisoner we will have two

for one as long as they last.

His officers now began to beg him most pitifully

not to fire, for if you do, said they, they will kill

us; they stand here around us with their knives

open, declaring if we stir one foot they will take

our lives. The president being permitted to come

to the port, begged his countrymen to shed no

blood on his account, for he did not desire to

remain on board the ship any longer, and he

entreated that for his sake the officers be

released. The officers were then released.

Double plank bulkheads at each end of our prison

rooms, with musket holes in them to fire in upon

us if necessary, separated us from the officers,

sailors and soldiers. Again we were asked if we

would receive our allowance of bread? No. Some

threats were thrown out by the prisoners that

he would hear from us before morning. About ten

o'clock at night, when all were quiet but the

guard and watch on deck, a torch light was got

up by setting some soap grease on fire in tin

pans. By the aid of this light, a heavy oak

stanchion was taken down which served us for

a battering-ram. Then with our large-empty tin

water cans for drums, and tin pails, kettles,

pans, pots, and spoons for drum sticks, and

whatever would make a stunning noise, the torch

lights and battering-ram moved onward to the

after bulkhead that separated us from the

commander and his officers, soldiers and their

families. For a few moments the ram was

applied with power, and so successfully that

consternation seized the sleepers, and they fled,

crying for help, declaring that the prisoners

were breaking through upon them. Without

stopping for them to rally and fire in upon us, a

rush was made for the forward bulkhead, where

a portion of the ship's company with their

families lived. The application of the battering

ram was quite as successful here, so that all our

enemies starving prisoners, devising the best

means for were now as wide awake as their

hungry, their defense. Here our torch-lights went

out, leaving us in total darkness in the midst of

our so far successful operations. We grouped

together in huddles, to sleep, if our enemies

would allow us, until another day should dawn to

enable us to use our little remaining strength in

obtaining if possible, our full allowance of bread

and water.

JOSEPH BATES.

Orleans, Ionia Co., Michigan

August. 1859.

INCIDENTS IN MY PAST LIFE No. 10.

Reconciliation. Full allowance of bread granted—

Cutting

a hole through the ship—Perilous adventure of

a Narragansett Indian—Hole finished Eighteen

prisoners escape—Singular device to keep the number

good.

THE welcome fresh air, and morning light came

suddenly upon us, by an order from the

commander to open our port-holes, unbar the

hatchways, and call the prisoners up to get

their bread. In a few moments it was clearly

understood that our enemies had capitulated by

yielding to our terms, and were now ready to

make peace by 'serving us with our full

allowance of bread.’ While one from each

mess of ten was up getting their three days'

allowance of brown loaves, others were up to

the tank filling their tin cans with water, so that

in a short space of time a great and wonderful

change had taken place in our midst. On most

amicable terms of peace with all our keepers,

grouped in messes of ten, with three days'

allowance of bread, and cans filled with water,

we ate and drank, laughed and shouted

immoderately over our great feast, and

vanquished foe. The wonder was that we did not

kill ourselves with over-eating and drinking.

The commissary, on hearing the state of things

in our midst, sent orders from the shore, to the

commander to serve out our bread forthwith.

Our keepers were in the habit of examining the

inside of our prison every evening before we

were ordered up to be counted down, to

ascertain whether we were cutting through the

ship to gain our liberty.

We observed that, they seldom stopped at a

certain place on the lower deck, but passed it

with a slight examination. On examining this

place, a number of us decided to cut a hole here

if we could effect it without detection by the

soldier who was stationed but a few inches

above where we must come out and yet have

room above water.

Having nothing better than a common table knife

fitted with teeth, after some time we sawed out

a heavy three-inch oak plank, which afterwards

served us successfully for a cover when our

keepers were approaching. We now began to

demolish a very heavy oak timber, splinter by

splinter. Even this had to be done with great

caution, that the soldier might not hear us on the

outside. While one was at work in his turn, some

others were watching that our keepers should

not approach and find the hole uncovered. About

forty were engaged in this work. Before the

heavy timber was splintered out, one of our

number obtained the cook's iron poker. This was

a great help to pry off small splinters around the

heavy iron bolts. In this way,after laboring

between thirty and forty days, we reached the

copper on the ship's bottom some two to three

feet from the top of our cover, on an angle at

about 25° downward. By working the poker

through the copper, on the upper side of the

hole, we learned to our joy that it came out

beneath the stage where the soldier stood. Then

on opening the lower side of the hole the water

flowed in some, but not in sufficient quantities

to sink the ship for some time, unless by change

of wind and weather, she became more

unsteady in her motion, and rolled the hole under

water, in which case we should doubtless have

been left to share her fate. The commander had

before this, stated that if by any means the ship

caught fire from our lights in the night, he would

throw the keys of our hatchways overboard, and

leave the ship and us to burn and perish

together. Hence we had chosen officers to

extinguish every light at 10 P. M.

Sunday P. M., while I was at work in my turn

enlarging the hole in the copper, a shout of

hundreds of voices from the outside so alarmed

me for fear that we were discovered, that in my

hurry to cover up the hole the poker slipped

from my hands through the hole into the sea. The

hole covered, we made our way with the rushing

crowd, up the long stairway to the upper deck,

to learn the cause of the shouting. The

circumstances were these:

Another ship like our own, containing American

prisoners, was moored about one eighth of a mile

from us. People from the country in their boats

were visiting the prison ships, as was their

custom on Sundays, to see what looking

creatures American prisoners were. Soldiers

with loaded muskets, about twenty feet apart, on

the lower and upper stages outside of the ship,

were guarding the prisoners' escape. One of the

countrymen's boats rowed by one man, lay

fastened to the lower stage, at the foot of the

main gangway ladder, where also one of these

soldiers was on guard. A tall, athletic

Narragansett Indian, who like the rest of his

country-men, was ready to risk his life for

liberty, caught sight of the boat, and watching

the English officers who were walking the

quarter deck, as they turned their backs to walk

off he bolted down the gangway ladder, clinched

the soldier, musket and all, and crowded him

under the seats, cleared the boat,

grasped the two oars, and with the man (who

most likely would have shot him before he could

clear himself) under his feet, he shaped his

course for the opposite unguarded shore, about

two miles distant!

The soldiers seeing their comrade with all his

ammunition, snatched from his post, and stowed

away in such a summary manner, and moving

out of their sight like a streak over the water by

the giant power of this North American Indian,

were either so stunned with amazement at the

scene before them, or it may be with fear of

another Indian after them, that they failed to hit

him with their shot. Well-manned boats with

sailors and soldiers were soon dashing after him,

firing and hallooing to bring him too; all of which

seemed only to animate and nerve him to ply his

oars with Herculean strength.

When his fellow-prisoners saw him moving away

from his pursuers in such a giant-like manner,

they shouted, and gave him three cheers. The

prisoners on board our ship followed with three

more. This was the noise which I had heard

while working at the hole. The officers were so

exasperated at this, that they declared if we did

not cease this cheering and noise they would

lock us down below. We therefore stifled our

voices, that we might be permitted to see the

poor Indian make his escape.

Before reaching the shore his pursuers gained on

him so that they shot him in his arm (as we were

told), which made it difficult to ply the oar;

nevertheless he reached the shore, sprang from

the boat, and cleared himself from all his

pursuers, and was soon out of the reach of all

their musket balls. Rising to our sight upon an

inclined plain, he rushed on, bounding over

hedges and ditches like a chased deer, and

without doubt would have been out of sight of

his pursuers in a few hours, and gained his

liberty, had not the people in the country rushed

upon him from various quarters, and delivered

him up to his pursuers, who brought him back

and for some days locked him up in the dungeon.

Poor Indian!

He deserved a better fate.

The prisoners now understood that the hole was

completed, and a great many were preparing to

make their escape. The committee men decided

that those who had labored to cut the hole

should have the privilege of going first. They also

selected four judicious and careful men, who

could not swim, to take charge of the hole and

help all out that wished to go.

With some difficulty we at length obtained some

tarred canvass, with which we made ourselves

small bags, just large enough to pack our jacket,

shirt and shoes in, then a stout string about ten

feet long fastened to the end, and the other end

made with a loop to pass around the neck. With

hat and pants on, and bag in one hand and the

other fast hold of our fellow, we took our rank

and file for a desperate effort for liberty. At the

given signal, (10 p. M.,) every light was

extinguished, and the men for liberty were in

their stations.

Soldiers, as already described, above and below

were on guard all around the ship with loaded

muskets.

Our landing place, if we reached it, about

half a mile distant, with a continued line of

soldiers just above high-water mark. The heads

of those who passed out, came only a few

inches from the soldier's feet, i. e., a grating

stage between.

A company of good singers stationed themselves

at, the after port-hole where the soldier stood

that was next, to the one over the hole. Their

interesting sailor, and war songs took the

attention of the two soldiers some, and a glass

of strong drink now and then drew them to the

port-hole, while those inside made believe drink.

While this was working, the committee were

putting the prisoners through feet foremost, and

as their bag string began to draw, they slipped

that out also, being thus assured that they were

shaping their course for the shore.

In the mean time when the ship's bell was

struck, denoting the lapse of another half-hour,

the soldiers' loud cry would resound, All's well!

The soldier that troubled us the most, would

take his station over the hole and shout, All's

well! Then when he stepped forward to hear the

sailors' song, the committee would put a few

more through, and he would step back and cry

again, All's well!! It surely was most cheering to

our friends while struggling for liberty in the

watery element, to hear behind and before them

the peace and safety cry, All's well!

Midnight came; the watch was changed, the

cheering music had ceased. The stillness that