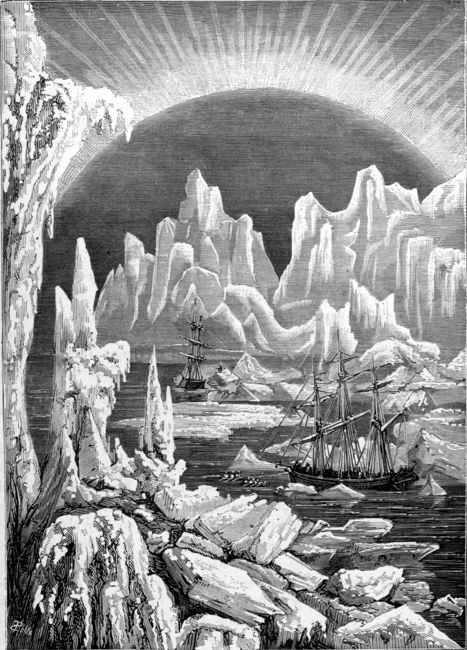

SIX MONTHS ON A CAKE OF ICE.

THE following is one of the most thrilling narratives on record. As a well-known writer has said, "There is nothing in all the records of peril and adventure which exceeds this." It is the history of nineteen persons, men, women, and children, who lived one hundred and ninety-five days, just six months and a half, upon cakes of ice in the Arctic Ocean, and were at last all saved: so wonderful are the mercies of God.

These poor ice-bound prisoners were a part of the crew of the United States Exploring Ship, Polaris, which was locked in the ice, in Smith's Straits, on the northwestern coast of Greenland. It was at the head of Baffin's Bay, away up in latitude 77° 35' north. The particulars of this narrative are as follows:

As there were alarming reasons for expecting that the Polaris would soon be crushed by the masses of ice, a large quantity of stores and provisions, with boats, instruments, etc., had been landed on the floe, and a canvas hut built for protection.

But scarcely had these measures for safety been taken, when the fury of a tempest suddenly broke up the ice, snapped the ship's cables, and rapidly bore her away from the floe.

This was in the night, and a blinding snowstorm was upon them. When the vessel thus suddenly disappeared, the men and stores floated off in various directions, and it was only after the most perilous exertions, occupying several hours' labor with the boats, that the people were finally collected on the main floe. About midnight, thankful that Heaven had spared them thus far, they all huddled together under the scanty protection of some musk-ox skins.

This was Oct. 15, 1872.In the morning after the separation, it was discovered that they were upon an ice floe about a mile and a half in diameter.

The party consisted of ten seamen, among them one of the ship's officers, two Es- quimaux men, with their wives, and five small children, one of them being a babe only two months old! His name was called Charles Polaris, after the ship, upon which he was born. For their subsistence, they had a quantity of canned meat, a few bags of bread, some dried apples, find a sack of chocolate. They had also guns and ammunition, two ship's boats, kyacks, various instruments of navigation, a tent, and several Esquimaux dogs. After taking some nourishment, the sailors took their boats and attempted to reach the shore near by, intending soon to return and get their stores; but the continued tempest and moving ice stopped them, and they were obliged to haul up their boats on a floe. To add to their distress, the Polaris was now seen under steam and sail several miles away.

A gale came sweeping down upon them, breaking up the floe, and separating them from one of their boats. They were now left upon a piece of ice only twenty or thirty rods across. Having abandoned all hope of reaching the vessel, they made back to the main floe, and began to prepare for the trials before them. Soon the ice, which had hitherto remained stationary among the bergs, began to drift, drift away, with its living freight upon it. Several snow huts were now built by the sailors, one of which was warmed by a lamp made out of a meat can, with a piece of canvas for wicking. Through a kind Providence, several seals were caught, which supplied them with both fuel and food. By the first of November the sun had completely disappeared, and they only had twilight, with the moon and stars, for many weeks. The floe party was soon reduced to very scanty rations of food; but they always managed to catch seals or other Arctic game, which saved them from actual starvation. Most of the dogs were shot, as they were too weak to be of use.

The 28th of November, Thanksgiving Day, was duly celebrated by the shipwrecked company. Their dinner was as follows: Six biscuits, a pound of canned meat, a little soup, and some preserved corn. Thus they feasted, thanking the Giver of all mercies.

Life upon the floe was very simple. Most of the time was spent in the snow huts, it being too dark to move about, even if there had been any motive. Thus the dreary month of December passed by with few events of interest. Christmas was celebrated by the extra allowance of an ounce of bread to each person to make the seal broth thicker.

New Year's day was the coldest that the party had experienced thus far. The thermometer was very low, not rising above 25°, and sometimes descending to 40° below zero. It was ice, ice, ice, in all directions, bergs, hummocks, floes, and packs; but still they drifted south along the eastern coast of Prince William's Land. They were now about halfway down Baffin's Bay.

About the middle of January two polar bears came to the huts, and attacked the dogs, but as might be expected, the dogs were so weak that they were quickly worsted in the contest. All this time the party were drifting slowly along, in sight of the western coast, which they judged to be from forty to seventy miles distant. The cold month of February was dismal indeed, but they occasionally caught a seal, which saved them from perishing. At this time they were drifting through Davis' Straits. But we have already exceeded our limits, and so defer the remainder of this narrative till next week.

G. W. AMADON.

SIX MONTHS ON A CAKE OF ICE.

THE month of March opened upon our voyagers with terrible severity, yet one of the men ventured out on the ice and shot sixty-six dovekies, a little Arctic Water-bird which weighs only three or four ounces. About this time the party were in very great apprehension by the grinding of the ice mountains, which sounded like heavy artillery. The floe also was being constantly reduced in size. The roaring of the gales, the collision of the bergs, the swashing of the water, and the breaking up of the floe, made their situation most terrible to contemplate. But the Guiding Hand had mercies still in store for them, and soon the weather moderated. Not far from this, when their food was all gone, and one of their boats burned up for fuel, the captain shot a polar bear, which saved them from starving. "Praise the Lord," writes one of the men, "this is his Heavenly work!

Food comes some way, when we must have it."

The last of March, observations were made, and they judged that they were opposite Cape Farewell, the most southern land of Greenland. Heavy Atlantic gales were now greatly reducing the floe in size, and they were also in a drowning condition. They now took to the boat in hopes of finding a larger piece of ice. They had also reached the place where vessels in quest of seals might be expected. After buffeting with ice and water for several hours, they hauled up on a small floe, and erected the canvas tent. At this time one of the Esquimaux shot a bear, which was ranging over the ice in search of seals.

This furnished them with a supply of food for a while. But the month of April was by far the most perilous time to the drifting party, in consequence of their being obliged to pass from floe to floe, as the ice would break. Sometimes the floe would suddenly separate, leaving the party on different pieces, and throwing them into the water.

At times they were obliged to keep the women and children in the boat, to be ready when the ice broke. Once they were compelled to hold on to the boat for above thirty hours in succession, to keep her from being washed off in a gale.

But there remained only a few more days of drifting, and waiting, and watching for the mariners. On the 28th, just at night, they descried a steamer in the distance, but could not attract her attention, and she bore away. Fires were now made on the ice, with seal blubber, to attract the attention of passing vessels. Again their spirits rose and fell by seeing a steamer several miles away, but she, too, soon passed out of sight, though they discharged all their guns to attract her attention.

But early on the following morning, when the fog lifted, a glorious sight met their anxious gaze! A steamer was discovered within a short distance of the floe. Guns were immediately fired, the colors were set, and loud and prolonged shouts were uttered. The vessel's head was soon turned toward them, and in a few moments she was alongside the floe. The continued cheers given by the shipwrecked party were returned by the shouts of a hundred strong men on deck and aloft. In a few moments they were all on board; yes, on board, and, thank Heaven, SAVED.

This providential deliverance occurred May 1, 1873. The vessel was the sealer Tigress, of Newfoundland. The floe-party was picked up off the coast of Labrador, in latitude 53° 35' north, and had consequently drifted through twenty-four degrees of latitude, and over a waste of ice and water some two thousand miles in length! *How wonderful are the ways of Providence with the needy children of men. In another article we will tell the readers what became of the Polaris, and the men left on board.

G. W. AMADON.

*NOTE. The particulars of this remarkable narrative are taken from a volume of 700 pages, prepared under the direction of the Secretary of the Navy, and published by the Government Printing Office at Washington.

WHAT BECAME OF THE POLARIS?

IN the preceding numbers the readers have learned about the separation of the crew of the Polaris, and how a part of them lived for over six months on cakes of ice, and were, at last, all saved. We will now tell what became of the Polaris, and the remnant of the crew that remained with her.

After the separation, the captain called all hands together, when it was found that only fourteen men remained on board.

The crew gazed for a few moments on each other in silence, when the duties of the ship were resumed. The vessel was rapidly driven through the water, and after some time ran into posh ice, and her progress was stayed. The ship was found to be leaking badly, but steam was gotten up, and the pumps gained on the leak.

In the morning, anxious eyes were on the lookout for the company who had been separated from them in the night; but they were obliged to attend at once to their own personal safety, as the ship was in a sinking condition. Under these circumstances they decided to run the vessel ashore, and abandon her. Having by the aid of steam and sail thrust the ship into the land, active preparations were made for leaving her.

This was October 17,1872.

They now built huts on the shore, and began to remove their effects. Soon they were visited by some Esquimaux, who came to the ship with a small sled drawn by dogs.

These natives were dressed in dog and bear skins. They were a good-natured set of fellows, and helped the seamen to move to the shore, which was some twenty rods distant. It was surprising to see what great loads their dogs could draw. Four of them would trot off gaily with a burden which as many sailors could barely move!

About this time the sun disappeared, and was out of sight till April; but they had twilight, and some of the time, most beautiful auroras. The crew were well off for provisions, but were very poorly provided with clothes, their goods being on the floe.

They had also only a limited supply of ammunition for their fire-arms.

It was soon decided to live as well as they could through the winter, and then build small boats out of the Polaris, and in the summer sail down the coast of Greenland, hoping to reach the Danish settlements, or better still, fall in with some whale men.

During the winter, they were visited by more than a hundred Esquimaux, with their families and sleds and dogs. The natives often furnished them with seals and walrus, which they were very skillful in capturing. The seamen also made very many excursions, to hunt and to explore the coast, and to take observations; for which last object they were provided by our government with the most approved instruments. Several of the party also were thoroughly scientific men. In their hunting excursions they shot numerous rabbits and foxes, geese, and other Arctic birds.

During the winter, by their constant intercourse with the natives, they had good opportunities for learning much in regard to their habits, religion, and ways, as a people.

By the first of January, the twilight had so increased that at noon observations were made without artificial light. At this time the grinding of the bergs in the Straits resembled continued thunder. The mate of the ship now commenced the constructionof two boats, with which to escape from this land of ice. Several weeks were occupied in building them, and furnishing them with sails made of sheets and towels.

On the 2d of June they commenced their perilous voyage amid the floating ice. For over three weeks they coasted southward, moving through the water by the aid of sails and oars, and hauling up on the shore ice, or rocks, to rest, as they were compelled. But on the 28th, the company, were electrified by hearing one of the men cry at the top of his voice, “Ship ahoy!" Joy thrilled every breast! Away to the south, some ten miles distant, were seen the three masts and smokestack of a vessel. This was one of the Scotch whalers, which they had hoped to fall in with. The flag was now hoisted on two oars, lashed together. Soon the ship's ensign was run up, showing that the signal was seen.

The Polaris men now dispatched two of their number to communicate with the strange vessel. When about half way, they were met by ten sailors, who had come out to render assistance. From them was learned the grateful intelligence that the party on the floe had been picked up. By midnight all hands were on board the vessel, which proved to be the Ravenscraig, of Scotland, Captain Alien commander. Here they were treated with the utmost kindness. By a prosperous passage, the entire crew in a few weeks reached the city of Washington, and one of the boats was preserved and exhibited at the great Centennial of 1876.

G. W. AMADON.

- Home

- A Beautiful Incident

- A Cure For Anger

- A Bad Habit

- A Baked Bible

- A Bible Story

- A Boy Rescued

- A Brief Narrative

- A Child Faith

- A Cure For Discontent

- A Curl Cut Off

- A Dark Picture

- A Dying Exhortation

- A Faithful Shepherd

- A Father To Child

- A Few Words

- A Good Name

- A Good Old Man

- A Lamb On The Battle

- A Little Heroine

- A More Excellent Way

- A Mother's Influence

- A Mother's prayer

- A Night In Log House

- A Painful But True

- A Poor Memory

- A Precious Gift

- A Sad Story

- A Short Lesson

- A Silent Teacher

- A Soft Answer

- A Story For Children

- A Story For Little Ones

- A Striking Question

- A Summer Day

- A Sure Helper

- A Talk With The Boys

- A Thankful Heart

- A Thoughtless Boy

- A True Story Of A Sailor

- A Walk Among Trees

- A Wonderful Machine

- About Getting Lost

- Advent Bible

- Aggie's New Friend

- Almenia A Deaf Girl

- An Anchor Of Safety

- An Escape From Drowning

- An Experience

- An Incident Of Slaves

- An Incident While Riding

- An Incident Of A Christian

- An Indian's Gift

- Are You Angry Pa

- Are You Ready

- Asking Father

- August In Old England

- Aunt Hagar On The Rock

- Autumn

- Bad Money

- Barren Tree

- Be Careful Of Your Words

- Be Firm

- Be Kind

- Be Kind In Little Things

- Be Kind To Thy Father

- Be Kind To Your Sister

- Be Merciful

- Be Punctual

- Be Slow To Accuse

- Beacon Lights

- Bees In Peru

- Benevolence

- Benevolence By Brothers

- Benevolent System

- Bertha's Graveyard

- Best Treasure

- Bird Studies

- Blind Girl

- Boy Would Not Get Mad

- Bread Upon The Waters

- Camel's Hump

- Carrie Gale's Disobedience

- Catching sunspots

- Charity

- Children Can Do Good

- Children Play With Bear

- Children's Fears

- Chip Reading

- Choices Foolish Wise

- Christ's New Little Girl

- Chuck Full Of The Bible

- Cling To Jesus

- Close Of The Year

- Come To Jesus

- Come Unto Me

- Coming Tide

- Consider

- Contentment

- Contentment Now

- Cornelia's Wish

- Cured By Kindness

- Curious Customs

- Cyrus

- Danger Of Procrastination

- Dear Children

- Dean Thomas

- Dear Children --Weep

- Dear Young Friends

- Deceitful Flowers

- December

- Delia

- Desire

- Died For Me

- Discipline

- Disobedience To Parents

- Do As You Would Be

- Do More For Mother

- Do You Know Jesus

- Do You Thank God

- Do You Want Religion

- Doing Good

- Don't Act A Lie

- Don't Be Too Certain

- Drowning The Squirrel

- Dying

- Each Can DO Some

- Eddie's Lunch Basket

- Eddie's Sermon

- Education And Crime

- Effects Of Reading

- Employment Of Time

- Escapes Of Rafaravy

- Even A Child

- Evil Practices

- Feel Like It

- Filial Kindness

- Finger Marks

- Five Answers

- For The Little Ones

- Forbid Them Not

- Forgiveness

- Four Pairs Of Hands

- Frank And Johnny

- Getting The Worst

- Giants

- Girls Help Your Father

- Go And Tell Jesus

- God Cares For Birds

- God's Footprints

- God Is Good

- God Protects His People

- God's Remembrance

- Golden Words

- Good For Nothing

- Gracie's Pennies

- Grandma's Story

- Grandpa's Fight

- Hand That Never Struck

- Happy Evening

- Happy For Three Pins

- Hark

- Hattie's New Dress

- Hauling The Seine

- Have Compassion

- Have You A Soul

- Have You Found Your Sin

- Having Courage

- He Could Be Trusted

- Heart And Tongue

- Heart Murder

- Heaven

- Help One Another

- Help Yourself

- Hide Me

- Hiding The Faults

- Hillel

- Hindoo Girl

- Home

- Honest Child

- Honesty

- Honor Father And Mother

- House Cleaning

- How I Came To Sabbath

- How I Enlisted

- How Needles Are

- How To Read Bible

- How To Work

- I am Going Home

- I Wait Till Morn

- I Cannot Sir

- I Didn't Think

- I Shall Kiss Mother

- Idle Words

- If One Lesson

- I'm 'Fraid

- Impressive Incident

- In Thee I Trust

- Influence Of Reading

- Invitation

- Jack Unruly Colt

- Jamie's Garden

- Jessie's Lesson

- Jesus Is Precious

- Jim Dick

- Joash

- Joseph Bates 1

- Joseph Bates 2

- Joseph Bates 3

- Joseph Bates 4

- Joseph Sold

- Kate's Forgiveness

- Kiss For A Blow

- Knitting

- Knud Iverson

- Lamb

- Language of The Cross

- Lantern

- Leaning On A Reed

- Learn To Trust

- Learning To Swear

- Led By A Child

- Lesson From Clock

- Let Children Pull

- Life Of Christ

- Life Of Christ 2

- Lift A Little

- Lillie's Birthday

- Little Blind Boy

- Little By Little

- Little Children

- Little Cords

- Little Freddy

- Little Jean

- Little Kindnesses

- Little Outcast

- Little Sins

- Little Things

- Little Wanderers

- Look At A Picture

- Look On The Bright

- Love Not The World

- Love Your Enemies

- Lucy's Victory

- Lydia And Brother

- Make Me A Christian

- Making Others Happy

- Mammoth Caves

- Martha Kinsley

- Meditation

- Meditations

- Miss Me

- Misspent Evenings

- Morning

- Mother Made It

- Mother Never Tells

- My Bible Poem

- My Childhood

- My Experience

- My Father's House

- My Master

- My Mother

- Never Hunch

- New Sight

- New Years Day

- New Years Gift

- Night Hawks

- No Perhaps

- Not Today

- Not Too Late

- Nothing But Leaves

- Nothing Lost

- Novel Fashion

- Obey God

- Obeying At Once

- Old Dog Grim

- Old Molly

- One Drop

- Only A Trifle

- Open The Prisons

- Our King

- Passing Away

- Paul's Victory

- Peace At Home

- Peaceful Sleep

- Pickets

- Please Yourself

- Pray Every Minute

- Prayer

- Prayer For Aaron

- Praying Child

- Pray Over Lessons

- Present Pleasure

- Pride

- Profanity

- Psalms 92-12

- Pull Adam Pull

- Ragged Tom

- Raining Gold

- Recollections

- Resurrection

- Riches Cannot

- Run Errands

- Ruth

- Sabbath Breaking

- Saint Patrick

- Save The Children

- Saved By Rain

- Secret Prayer

- Semiramis

- Seventy Times

- She Was A Stranger

- Short Lecture 1

- Short Lectures 2

- Sin Brings Death

- Sin Found Out

- Snow

- Somebody Loves Me

- Song Birds

- Spare Moments

- Speak The Truth

- Strong Character

- Strong In Him

- Take Care

- Talking To Jesus

- Tekel

- Tell A Lie

- Temptation

- The Broken Saw

- The Garden Of Peace

- The Peacemaker

- The Praying Girl

- The Prussian Girl

- The Sisters

- The Almond Blossoms

- The Apostle Paul

- The Barefoot Boy

- The Beautiful

- The Beggar Boy

- The Best Riches

- The Big Umbrella

- The Black Lamb

- The Boy At The Gate

- The Boy's Triumph

- The Broken Plate

- The Charmer

- The Child And Butterfly

- The Child's Answer

- The Child's Gospel

- The Circus

- The Cocoa Nut Tree

- The Comforting Hope

- The Contribution

- The Converted Negro

- The Curious Dish

- The Distrustful Bird

- The Dragon Fly

- The Earlier The Easier

- The Example Of Jesus

- The Eye Servant

- The Fall Of Pemberton

- The First Command

- The Five Peaches

- The Flower Fadeth

- The Flower Of Pleasure

- The Friend

- The Golden Pennies

- The Golden Rule

- The Grateful Tiger

- The Hinge Maker

- The Handsome Cloak

- The Heroic Servant

- The Jungle Boy

- The Lamb

- The Last Dollar

- The Liar

- The Little Blind Girl

- The Little Captives

- The Little Loaf

- The Little Swearer

- The Swiss Girl

- The Little Truant

- The Lost Boys

- The Lost Child

- The Lost Fellow

- The Lost Children

- The Man In The Dark

- The Mocking Bird

- The Narrow Way

- The Fishermen

- The Persevering Boy

- The Prayer Girl

- The Poor Slave

- The Prince And Serfs

- The Rebuke

- The Repose Of Flower

- The Robin

- The Signal Gun

- The Sleigh Ride

- The Snow

- The Squirrel Rights

- The Story Of Redemption

- The Strawberries

- The Struggle And Victory

- The Teacher's Return

- The Third Commandment

- The Three Boys

- The Turnover

- The Two Sons

- The Way

- The Well Never Dries

- The Widow's Prayer

- The Widow

- The Widow's Son

- The Wonderful Water

- The Works Of God

- The Worst Being

- They Say

- Thou God Seest

- Three Helps

- Thunder Storms

- The Little Worm Ped

- To The Boys

- To The Young

- Tower Of Repentance

- Traveler

- Tread Under Foot

- Tree Never Fades

- Trot Foot

- True Riches

- True Courage

- Trust The Lord

- Two Little Girls

- Two Faces

- Two Inheritances

- Two Proverbs

- Two Voices

- Unchecked Growth

- Uncle Crisp

- Unsaid Words

- Unseen influences

- Vain Thoughts

- Value Of Perseverence

- Waiting

- What The Clock say

- What God Has Done

- What Have you Done

- What Will Jesus Say

- What Makes A Man

- What Malachi Says

- What Grasshoppers Did

- What To Read

- What Two Apples Did

- When May Children

- Where Is Your Treasure

- Who Are Associates

- Who Prays

- Willie's Faith

- Without Affection

- Woodland Rambles

- Work For Sabbath School

- Yield A Little

- Young Christian Reflection

- The Drowned God

- David Hume

- The Holy Coat

- A Beam

- A Beautiful Answer

- A Beautiful Incident 2

- A Boy's Leisure Hours

- A Brave Boy

- A Coffee Field

- A Curious Instrument

- A Fortified City

- A Fortune Book

- A Glimpse Of Cal

- A Guilty Conscience

- A Happy New Year

- A High Standard

- A Hot Water River

- A Lesson From Snail

- A Little Boy Sermon

- A Little Candle

- A Little Child

- A Little Errand

- A Little Hero

- A Little Self

- A Novel Perfume

- A Plant With No Stalk

- A Pleasant Occasion

- A Prize Character

- A Rich Man

- A Ropewalk

- A Sabbath Stone

- A School Girl

- A Scientific Wonder

- A Sealed Postman

- A Sermon On Light

- A Sermon On Push

- A Sketch Of History

- A Sleigh Ride

- A Strange Ambition

- A Strange Clock

- A Syrian Family

- A Terrific Storm

- A Thorn In The Pillow

- A Visit To London

- A Walking Leaf

- A Wonderful Clock

- A Wonderful Stick

- A Word Spoken

- A Word For Boys

- About Proving

- About Watches

- Absalom's Rebellion

- Acquaint Now Thyself

- Acting From Principle

- After Ahab Died

- Ahab's Wicked Reign

- Ahaz And Hezekiah

- AI

- Alexandria

- Among The Flowers

- Among The Roses

- Amusements

- An Awful Story

- An Important Question

- An Old Man

- Ancient Mounds

- Antiochus Epiphanes

- Antiquity Of Umbrellas

- Archery

- Are You Growing

- Asa

- Asa's Good Reign

- Aunt Lizzie's Story

- Bad Promises

- Bank Note

- Be Prompt

- Be Sure Your Sin

- Be True

- Beautiful Thoughts

- Behind Time

- Benhadad's Defeat

- Bernard Palissy

- Blessed Are Peace

- Blindness

- Butter Making

- Capernaum

- Carmel

- Carried Away

- Changes

- Character

- Children Voices

- Chinese In California

- Chinese Politeness

- Chinese Stories

- Christian Obedience

- Christmas Time

- Chromos

- Cinnamon Trees

- Clean Inside

- Cleopatra's Needle

- Colorado

- Come Inside

- Confidence

- Contemporary History

- Correct Speech

- Cost Of Tobacco

- Covenant

- Daily Bread

- Daisy's Flowers

- Daniel

- David's Flight

- David And Goliath

- David Maydole

- David Numbers The People

- David's Charge

- David's Desire

- David's Sin

- Dead Languages

- Death Of Eli

- Deborah And Barak

- Deliverance

- Demand

- Departure

- Did He Tell A Lie

- Disagreeable Habits

- Discovery Of Gas

- Do You Love Back

- Do You Match

- Do Your Best

- Dreams

- Drifting

- Droll Doings

- Eastern Beds

- Elijah Brings Fire

- Elijah Prays For Rain

- Elijah Raises The Dead

- Elijah Taken To Heaven

- Elise Le Mont

- Elisha's Miracles

- Ella's Garden

- Ellens Key

- Emery Ore

- Esdraelon

- Every Day Heroism

- Exaggeration

- Eyes And No Eyes

- Facts About Varnish

- Faith

- Famine In Samaria

- Filial Love

- First Lessons

- Fitly Answered

- Floating Gardens

- Florie's Birthday

- Follow Copy

- Foolscap Paper

- For Boys

- For Christ's Sake

- For Me

- Fords Of Jordan

- Forgive

- Freedom For Pets

- From History Abraham

- From History Jews Captive

- From History Rome Builds

- From History Rome

- From History State

- From History Jerusalem

- From Sea To Sea 1

- From Sea To Sea 2

- Gedaliah

- George's Reason

- Gideon And The Angel

- Gideon's army

- Girls Look Here

- Glass Garments

- Go Because It Rains

- God's Acre

- God's Care

- God's Life Book

- Gold and Silver Mine

- Golden Moments

- Good Advice

- Good Resolutions

- Grandmother's Visit

- Grandpa's Example

- HALLELUJAH

- Harry's Lesson

- Harry's Stratagem

- Have A Choice

- Herod The Great

- Herrings For Nothing

- History Of Bells

- Hitting The Mark

- Honesty Rewarded

- Honor Bright

- Honor Thy Father

- How Do You Meet

- How Many Were There

- How Rain Is Formed

- How Rubber Shoes

- How Slate Pencils

- How Strong Is God

- How Sunday School

- How The Fuchsia

- How The Months

- How To Be Gentleman

- How To Be Beautiful

- How To Read

- How To See A Seed

- How To Thank

- How To Treat Brother

- Hungry Children Fed

- I am The Shepherd

- I Am Bid

- I Prayed For Them

- Illusions

- In Another Battle

- In The Streets

- In The Sunshine

- Incidents Of Wilder

- Independence Day

- Indian Corn

- Influence

- Iron Swims

- Iron Shod

- Is There A God

- Is Your Note Good

- Israel Cross Jordan

- Israel Multiplies

- It Comes From Above

- It Isn't Mine

- It's Ours

- Jehoshaphat

- Jehu

- Jericho

- Jeroboam Leads

- Jerusalem Destroyed

- Jerusalem

- Jessie's Help

- Jews

- John's Account

- Johnny

- Jonah's Preaching

- Josiah

- Jotham

- Judging Israel

- June

- Just Caught

- Keep A Light

- Keep Thyself Pure

- Keep Your Promise

- Keep His Word

- Kindness

- King And Queen

- King Belshazzar

- Kings Of Judah

- Knocking Knees

- Known By His Walk

- Lamp To My Feet

- Learn To Remember

- Learn To Think

- Learning

- Leaves

- Lesson

- Life's Great Object

- Life A Failure

- Life Of Our Saviour

- Lighthouses

- Listen Carefully

- Little Christians

- Little Margaret

- Little Scotch

- Little Such Things

- 'LL No Trust Ye

- Look Out

- Looking For Papa

- Lucky Friday

- Luther Snow Song

- Mabel's Secret

- Make Home Pleasant

- Make Some Happy

- Make Sabbath

- Make Beginning

- Making Sunshine

- Manasseh

- Manasseh-Josiah

- Manner Of Burial

- Manners

- Maple Sugar

- Marble Block

- Martyrdom

- Maude And Lizzie

- May And Might

- Measureless Love

- Mercy And Wrath

- Milan Cathedral

- Mine And Thine

- Miss Vanity

- Mistakes

- More War

- Mother

- Mourning

- Mount Carmel

- Murmured

- Music

- Naaman The Syrian

- Naboth's Vineyard

- Name

- Nature

- Nature's Spring

- Nazareth

- Nebuchadnezzar

- Nehemiah

- Ninety And Nine

- NO

- Nobleman

- Notes On Bible

- Novel Playhouse

- Novel Reading

- Now Here

- Nutmegs

- Obey Mother

- OH I Forgot

- Oil On Water

- Old Testament

- Only A Pin

- Oranges

- Origin Of Plants

- Origin Of Christmas

- Our Christ

- Our Daily Cup

- Our Blessings

- Our Little Washer

- Our Lord's Miracles

- Our Thoughts

- Over In A Minute

- Overcoming

- Palestine

- Palestine Features

- Palms

- Paper Barrels

- Passages In Garfield

- Patience

- Paul's Lesson

- Pay Your Debt

- Pearls

- Pearl's Thanks

- Perfect Faith

- Perpetual

- Philip And Effie

- Pins

- Pins And Needles

- Plan To Come

- Plants

- Pleasures

- Plums

- Powers Of The Air

- Prayer Answered

- Present Truth

- Presidential Electors

- Prophecy Of Babylon

- Prophet Daniel

- Prosperous Belgium

- Protected

- Proud King

- Province Of Galilee

- Pull Together

- Queer Tom

- Raising Tomatoes

- Ransoms

- Rapids

- Read The Bible

- Real Presents

- Rebellion

- Rebuild The Temple

- Recapitulation

- Rehoboam

- Remember Ebal

- Repentance

- Resolution No 3

- Rest

- Results Of Accidents

- Return Of Jews

- Ride Through Kent

- Right To The Habit

- River

- Rob's Magic Mirror

- Rocky Mountain

- Rome And Britain

- Rosetta Stone

- Royal Guests

- Ruined

- Rural Life

- Sackcloth Ashes

- Samaria

- Samuel And David

- Samuel's Call

- Samuel Reproves

- Samuel's Prayer

- Saul Anointed

- Saul Then David

- Says So

- Scenes Of Galilee

- Scraps From History

- Secret Meeting

- Seed By The Way

- Seed Sown

- Self Respect

- Sewing Aches

- Shall We Pray

- Shut Eyes Tight

- Signal Lights

- Silent Influence

- Silver Smelting

- Simple Kra's Gift

- Sin

- Sitting Up

- Six Months On Ice

- Sketch Of Babylon

- Slide Along

- So How Long

- So Only A Flower

- Soap Bubbles

- Societies

- Solomon

- Some Advice

- Some Day

- Somebody

- Something For Girls

- Something New

- Something To Carry

- Somewhere Blue Sky

- Sowing Little Seeds

- Sowing Time

- Splicing The Ladder

- Standing For Right

- Stars

- Stick To Your Tree

- Story Of Flower

- Strange Food

- Strike The Knot

- Striking

- Sugar Making

- Surnames

- Susie's Exam

- Syrian Army

- Tabernacle

- Talk It Over

- Taught

- Teach The Samaritans

- Teacher Is Hidden

- Tell Your Mother

- Telling The Lord

- Temple

- Tested

- Texas

- That's How

- The Aborigines

- The Accurate Boy

- The Air

- The Anchor

- The Apostle John

- The Baptism

- The Baptist

- The Bible

- The Bible The Root

- The Bird Of Two

- The Birth Of Christ

- The Birth Of John

- The Black Rock

- The Blue Bead

- The Book Of Nature

- The Boyhood Of Jesus

- The Burial Of Joseph

- The Buttes

- The Call Of Matthew

- The Captain Slain

- The Carpet Weaver

- The Celestial Road

- The Child Dyke

- The Clam

- The Climate

- The Color Of Gem

- The Cost Of Care

- The Cousins

- The Crown Of England

- The Dedication

- The Difference

- The Dream Fulfilled

- The Fiery Furnace

- The First Newspaper

- The First Fruit

- The First Miracle

- The First Prayer

- The First Psalm

- The First Snow

- The First Step

- The First Wrong

- The Flight

- The Fresh Hour

- The Garden

- The Gate Shut

- The Giant Sin

- The Gibeonites

- The Gift Of God

- The Gospel Alphabet

- The Great Master

- The Great Wall

- The Gulf Stream

- The Halfway Place

- The Hardest Thing

- The Healed Servant

- The Heart Gardens

- The Holy Land

- The Homes Of Jesus

- The Ignis Fatuus

- The Influence

- The Irish Boy

- The Isle Of Cyprus

- The Jingle Bells

- The Kingdom Divided

- The Land Of Moab

- The Last

- The Leading Hand

- The Left Glove

- The Light

- The Lighthouse

- The Little Baby

- The Little Girl

- The Little Orphans

- The Little Songstress

- The Logic Of Life

- The Lord Knoweth

- The Lord Is God

- The Losings Bank

- The Lost Boy

- The Lotus

- The Maccabees

- The Magnet

- The Man Who

- The Microscope

- The Midnight Sun

- The Milk Tree

- The Moment Of Peril

- The Moon

- The Mount

- The Mysteries

- The Native Of Kilda

- The Natural Bridge

- The Nettle Tree

- The New Dress

- The Nobleman

- The Northern Lights

- The Old Monk

- The Old School

- The Oldest Book

- The Passover

- The Passover 2

- The People Of Arabia

- The Picnic

- The Planet Mercury

- The Preacher John

- The Present

- The Price Paid

- The Privilege

- The Prophet Jeremiah

- The Prophets

- The Pyramids

- The Resurrection

- The Rich Noble

- The River Jordan

- The River Nile

- The Runaway

- The Sabbath Cradle

- The Safe Retreat

- The Sailor Boy

- The Saviour's Invitation

- The School

- The Sea Of Galilee

- The Second Passover

- The Second Temple

- The Seven Wonders

- The Shipwrecked

- The Shunammite

- The Sin Of Lying

- The Skeptic

- The Sleep Of Flowers

- The Snowball

- The Sowing

- The Spring Comes

- The Starry Crowns

- The Stepping Stones

- The Stinging Tree

- The Stone Lamb

- The Sunbeam

- The Testimony

- The Three Sieves

- The Time To Be

- The Time

- The Tongue

- The Traveler's Tree

- The True Riches

- The Twelve Apostles

- The Useful Plant

- The Victoria Regia

- The Visit Of Wisemen

- The Waldensian

- The Water Lily

- The Water Mill

- The Way Effie Helped

- The Whole Class

- The Wilderness

- The Willful Boy

- The Woman

- The Wonderful Asbestos

- The Yosemite Valley

- The Young Gardener

- There Is One God

- These Little Strings

- Thine Is The Power

- This Coal Oil Johnny

- This Is Given

- Though Fearful

- Those Giant Mts

- Thoughtful

- Thoughtless Fun

- Three Hands

- Throne Of Judah

- Time

- Time To Study

- Tis For Love

- To Avoid Bad Books

- To Be Sure

- To Bear Burdens

- To Egypt

- To Galilee

- To Help People

- To Love

- To Smyrna

- Tobacco

- Tommy's Rabbits

- Too Bad

- Too Late

- Touch Of Faith

- Town Of Bethlehem

- Trip To California

- Triumphal Arches

- Troubles

- True Boy

- True Gentlemen

- Trust In Jesus

- Truth

- Try It

- Two Good Hands

- Two Of Ned's Rudders

- Two Poisons

- Two Ways

- Tyre And Sidon

- Unbelief

- Under The Sea

- Valley Of Petra

- Vast Colorado

- Very Fast

- Very Good Habit

- Very Sad Lesson

- Victory

- Visit To A Poet

- Visit To Nazareth

- Vitality Of Seeds

- Walter Entertained

- Want God's Pictures

- Watches

- Waves

- Wayside Scenes

- Wait Till You Know

- Wardrobe

- Water

- Well

- Well Do You Know

- Westward Bound

- Wharf

- What A Brave Boy

- What Came Of It

- What Have I Done

- What Is Sweeter

- What Is Your Copy

- What Kelsey Learned

- What Made Two--

- What The Rain Taught

- What To Give

- Wheat

- Wheat Fields

- When Knives

- When The Last Rays

- Where Alsatian

- Where Are The Cliff

- Where Is My Influence

- Where Is That Boy

- Where Jesus Taught

- Which Seed Are You

- Which Is Penitent

- Which Way Do You

- Who Will Be Ready

- Whom Can You Trust

- Why Are There Three

- Why Did He Learn

- Why Was Ethel

- Why Not Keep

- Why Was Christ

- Wicked Thoughts

- Wide Circuit

- Wild Flowers

- Wilderness

- Will And A Way

- Will He Succeed

- Will

- Willie's Violets

- Windsor Castle

- Wish

- Wolf Monument

- Wonderful Clock

- Wonderful Mother

- Wonderful Sights

- Wood

- Words To Girls

- Words To Boys

- Work

- Work Attention

- Work Before Play

- Work For All

- Work Footprints

- Working Dreaming

- Worthy Humble

- Wreckers

- Wycliffe

- Yearning For Jesus

- Yes My Grace Is

- Yet Not Useless

- Yosemite Valley

- You Better Watch Out

- You Can Consider

- You Are A Little

- Your Parents

- Your Word Is Sufficient

- Youth

- Youth Instructor

- Youthful Manners

- Zest Of Rice

- A Carpet

- A cross-look

- A grape-gatherer

- A dripping-well

- A Queer Way

- A Single Worm

- A Very Bad Habit

- A Walled Lake

- A Waterfall

- Abideth Forever

- Alice's Talent

- Curious Plants

- Curious Watches

- Five Cents

- Gethsemane

- Heal The Paralytic

- How Clinton

- How Children Play

- How Tower Clocks

- Jerusalem Now

- Still The Tempest

- John's Object Lesson

- Lot's Wife

- Mozart

- Origin Of Names

- Patience And Charity

- Perfect Trust

- Pleasant

- Power Of Voice

- Prove It

- Remember The Sabbath

- Resisted

- She Could

- Sketches Holy Land

- Tea Gardens

- The Clock Ticking

- The Dead Sea

- The Death Of John

- The Death Of Presidents

- The Disciples

- The Great Cataract

- The Gypsies

- The Japanese

- The Mustard Tree

- The Northern Sea

- The Orphan's Friend

- The Phoenician Coast

- The Power

- The Regalia

- The Thousand Islands

- True Politeness

- We Wanted To Come

- What Nettie Needed

- What The Flowers Said

- Why Everybody Is Cross