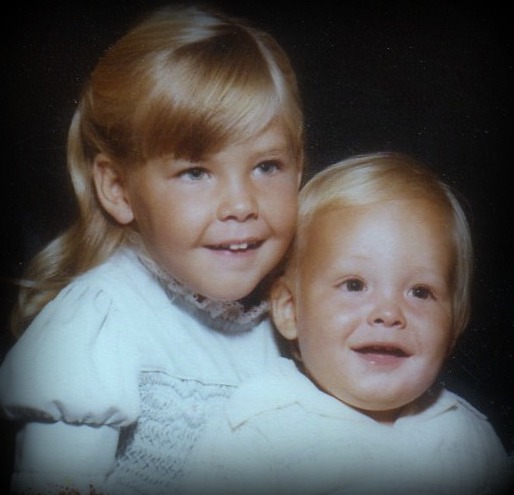

The Sisters.

A MOTHER called her two little girls to her

room one pleasant morning, and said, "I'm

sorry, but one of you will have to stay at

home today, my dears, for Jane's father

is sick, and I promised her that she should

go to see him; and I cannot take the care

of Eddie all day."

Of course she could not. You had only

to look into her pale face, and on her thin

weak body, to know that.

As her two little girls, Fanny and Alice

were standing before her when she said this

she saw their countenances fall. ''I wish

it were not so," the mother added feeble:

"but I would be in bed, sick, before the day

was half over, if I were left alone with

Eddie. Someone has to look after him all the

time."

Fanny pouted and scowled, I am sorry to

say, and Alice looked sober and

disappointed. They went from their mother's

room without speaking. When so far away

that she thought her voice could not be

heard by her mother, Fanny said, in a

sharp, resolute tone, from which all kind

feeling had died out:

"I'm not going to stay at home, Miss

Alice! You can make up your mind to

that."

Alice did not reply, but she sat down

quietly. Her disappointment was keen, for

some little girls in the neighborhood had

made up a small picnic party and were

going to have a pleasant day in the woods.

"It will be as mother says," she spoke

out, after thinking for a while.

"I'm the oldest, and have the best right

to go," answered Fanny, selfishly. "And

what's more, I'm going;" and she

commenced putting on her things.

A few tears crept into the eyes of Alice,

it would fall upon her to stay at home.

Fanny was selfish and strong-willed, and

unless positively ordered by her mother to

remain at home and let her sister go, would

grasp as her own the pleasure to which

Alice had an equal right with herself. If

the decision were referred to her mother, a

contention would spring up, and then Fanny

would speak and act in a way to cause her

distress of mind.

"If mother should make Fanny stay at

home," Alice said, in her thoughts, "she

would pout, and fling, and act so ugly that

there'd be no comfort with her; and mother

isn't strong enough to bear it."

The tender love that Alice held in her

heart for both her mother and dear little

two-year-old brother Eddie, was all-pervading.

and soon turned her thoughts away

from the picnic and its promised delights,

of the pleasures and loving duties of home.

"I'm going to stay," she said, coming

back into her mother's room with a bright

face and cheerful voice.

"Are you, dear?" It was all she said,

but in her tone and looks there was a

precious heart reward for Alice.

"He has been so sweet all day!" said

Alice, coming in where her mother sat by a

window with the cool airs of the late after-

noon fanning her wasted cheeks. She had

a weary look.

"And you have been sweet, too, my

darling!" answered her mother, in a very

tender voice, as she laid her hand on Alice's

head. "I don't know what I should have

done without you. It has been one of my

weak days. But you look tired, dear, "she

added. "Sit down in that easy chair and

rest yourself. Come, Eddie."

And she held out her hands for the child,

but he clambered into Alice's lap, and laid

his cunning little head against her bosom.

Both were tired, loving sister and pet

brother. It seemed hardly a minute before

they were asleep; and as the mother, with

her eyes that were fast growing dim, looked

at the tranquil faces and quiet forms, she

thanked God for such a precious gift.

Bang! Went the door, starting the mother

from peaceful thoughts, and arousing Alice

from the light slumber into which she had

fallen. In came Fanny, all in disorder, and

threw herself into a chair, looking the

picture of unhappiness.

"Have you had a pleasant time?" asked

the mother, speaking with a kind interest

in her voice.

"I've had a horrid time!" answered

Fanny, flinging out the words angrily. "I

never saw such a mean set of girls in my

life. They wouldn't do anything I wanted

to do, nor go anywhere I wanted to go."

"That was bad," said the mother. "And

suppose you wouldn't do anything they

wanted to do, nor go anywhere they wanted

to go?"

Fanny did not reply.

"How was it, my child?" urged the

mother.

"Hadn't I as much right to have my

way about things as any of them?"

demanded Fanny. "There was that Kate

Lewis I can't bear her. If she said, 'Let

us do this, or let us do that,' every one

agreed in a minute."

"You with the rest?" said the mother.

"Indeed, I did not!" replied Fanny,

impatiently. "That Kate Lewis can't lead

me about by the nose, as she does other

girls. I have a mind of my own."

"Perhaps," answered the mother,

seriously, "you would have come nearer to

the truth, my child, if you had said a self-

will of your own. I find, from your account

of things, that you wanted everything your

own way, and because the rest would not

give up to you, you made yourself disagreeable

and unhappy, and so lost all the pleasure

of the day. I'm afraid you were not

in just the best state of mind for enjoyment

when you left home this morning."

This was too much for Fanny, already

feeling so miserable; she broke out into a

fit of sobbing and crying.

In what different conditions of mind were

the two girls at the close of this day! Alice,

wakened from a brief, but refreshing,

sleep by the entrance of Fanny, sat, with

tranquil heart and peaceful face, looking at

her unhappy sister, who had selfishly claimed

the day for pleasure, not caring how wearily

it might pass for her, and pitied her

miserable condition, while Fanny cried from

very shame and wretchedness.

Dear little readers, need I ask any of

you, even the youngest, what made all this

difference? You have come to know,

through some painful as well as pleasant

experiences, that happiness waits not on

any selfish demand, but creeps lovingly into

every heart, which, forgetful of its own ease,

or comfort, or pleasure, seeks the comfort

and blessing of others.

Do not forget this, dear children. Keep

it always in mind, and it will not only save

you many unhappy hours, but put warm

floods of sunshine and joy into your hearts.

Children's Hour.

- Home

- A Beautiful Incident

- A Cure For Anger

- A Bad Habit

- A Baked Bible

- A Bible Story

- A Boy Rescued

- A Brief Narrative

- A Child Faith

- A Cure For Discontent

- A Curl Cut Off

- A Dark Picture

- A Dying Exhortation

- A Faithful Shepherd

- A Father To Child

- A Few Words

- A Good Name

- A Good Old Man

- A Lamb On The Battle

- A Little Heroine

- A More Excellent Way

- A Mother's Influence

- A Mother's prayer

- A Night In Log House

- A Painful But True

- A Poor Memory

- A Precious Gift

- A Sad Story

- A Short Lesson

- A Silent Teacher

- A Soft Answer

- A Story For Children

- A Story For Little Ones

- A Striking Question

- A Summer Day

- A Sure Helper

- A Talk With The Boys

- A Thankful Heart

- A Thoughtless Boy

- A True Story Of A Sailor

- A Walk Among Trees

- A Wonderful Machine

- About Getting Lost

- Advent Bible

- Aggie's New Friend

- Almenia A Deaf Girl

- An Anchor Of Safety

- An Escape From Drowning

- An Experience

- An Incident Of Slaves

- An Incident While Riding

- An Incident Of A Christian

- An Indian's Gift

- Are You Angry Pa

- Are You Ready

- Asking Father

- August In Old England

- Aunt Hagar On The Rock

- Autumn

- Bad Money

- Barren Tree

- Be Careful Of Your Words

- Be Firm

- Be Kind

- Be Kind In Little Things

- Be Kind To Thy Father

- Be Kind To Your Sister

- Be Merciful

- Be Punctual

- Be Slow To Accuse

- Beacon Lights

- Bees In Peru

- Benevolence

- Benevolence By Brothers

- Benevolent System

- Bertha's Graveyard

- Best Treasure

- Bird Studies

- Blind Girl

- Boy Would Not Get Mad

- Bread Upon The Waters

- Camel's Hump

- Carrie Gale's Disobedience

- Catching sunspots

- Charity

- Children Can Do Good

- Children Play With Bear

- Children's Fears

- Chip Reading

- Choices Foolish Wise

- Christ's New Little Girl

- Chuck Full Of The Bible

- Cling To Jesus

- Close Of The Year

- Come To Jesus

- Come Unto Me

- Coming Tide

- Consider

- Contentment

- Contentment Now

- Cornelia's Wish

- Cured By Kindness

- Curious Customs

- Cyrus

- Danger Of Procrastination

- Dear Children

- Dean Thomas

- Dear Children --Weep

- Dear Young Friends

- Deceitful Flowers

- December

- Delia

- Desire

- Died For Me

- Discipline

- Disobedience To Parents

- Do As You Would Be

- Do More For Mother

- Do You Know Jesus

- Do You Thank God

- Do You Want Religion

- Doing Good

- Don't Act A Lie

- Don't Be Too Certain

- Drowning The Squirrel

- Dying

- Each Can DO Some

- Eddie's Lunch Basket

- Eddie's Sermon

- Education And Crime

- Effects Of Reading

- Employment Of Time

- Escapes Of Rafaravy

- Even A Child

- Evil Practices

- Feel Like It

- Filial Kindness

- Finger Marks

- Five Answers

- For The Little Ones

- Forbid Them Not

- Forgiveness

- Four Pairs Of Hands

- Frank And Johnny

- Getting The Worst

- Giants

- Girls Help Your Father

- Go And Tell Jesus

- God Cares For Birds

- God's Footprints

- God Is Good

- God Protects His People

- God's Remembrance

- Golden Words

- Good For Nothing

- Gracie's Pennies

- Grandma's Story

- Grandpa's Fight

- Hand That Never Struck

- Happy Evening

- Happy For Three Pins

- Hark

- Hattie's New Dress

- Hauling The Seine

- Have Compassion

- Have You A Soul

- Have You Found Your Sin

- Having Courage

- He Could Be Trusted

- Heart And Tongue

- Heart Murder

- Heaven

- Help One Another

- Help Yourself

- Hide Me

- Hiding The Faults

- Hillel

- Hindoo Girl

- Home

- Honest Child

- Honesty

- Honor Father And Mother

- House Cleaning

- How I Came To Sabbath

- How I Enlisted

- How Needles Are

- How To Read Bible

- How To Work

- I am Going Home

- I Wait Till Morn

- I Cannot Sir

- I Didn't Think

- I Shall Kiss Mother

- Idle Words

- If One Lesson

- I'm 'Fraid

- Impressive Incident

- In Thee I Trust

- Influence Of Reading

- Invitation

- Jack Unruly Colt

- Jamie's Garden

- Jessie's Lesson

- Jesus Is Precious

- Jim Dick

- Joash

- Joseph Bates 1

- Joseph Bates 2

- Joseph Bates 3

- Joseph Bates 4

- Joseph Sold

- Kate's Forgiveness

- Kiss For A Blow

- Knitting

- Knud Iverson

- Lamb

- Language of The Cross

- Lantern

- Leaning On A Reed

- Learn To Trust

- Learning To Swear

- Led By A Child

- Lesson From Clock

- Let Children Pull

- Life Of Christ

- Life Of Christ 2

- Lift A Little

- Lillie's Birthday

- Little Blind Boy

- Little By Little

- Little Children

- Little Cords

- Little Freddy

- Little Jean

- Little Kindnesses

- Little Outcast

- Little Sins

- Little Things

- Little Wanderers

- Look At A Picture

- Look On The Bright

- Love Not The World

- Love Your Enemies

- Lucy's Victory

- Lydia And Brother

- Make Me A Christian

- Making Others Happy

- Mammoth Caves

- Martha Kinsley

- Meditation

- Meditations

- Miss Me

- Misspent Evenings

- Morning

- Mother Made It

- Mother Never Tells

- My Bible Poem

- My Childhood

- My Experience

- My Father's House

- My Master

- My Mother

- Never Hunch

- New Sight

- New Years Day

- New Years Gift

- Night Hawks

- No Perhaps

- Not Today

- Not Too Late

- Nothing But Leaves

- Nothing Lost

- Novel Fashion

- Obey God

- Obeying At Once

- Old Dog Grim

- Old Molly

- One Drop

- Only A Trifle

- Open The Prisons

- Our King

- Passing Away

- Paul's Victory

- Peace At Home

- Peaceful Sleep

- Pickets

- Please Yourself

- Pray Every Minute

- Prayer

- Prayer For Aaron

- Praying Child

- Pray Over Lessons

- Present Pleasure

- Pride

- Profanity

- Psalms 92-12

- Pull Adam Pull

- Ragged Tom

- Raining Gold

- Recollections

- Resurrection

- Riches Cannot

- Run Errands

- Ruth

- Sabbath Breaking

- Saint Patrick

- Save The Children

- Saved By Rain

- Secret Prayer

- Semiramis

- Seventy Times

- She Was A Stranger

- Short Lecture 1

- Short Lectures 2

- Sin Brings Death

- Sin Found Out

- Snow

- Somebody Loves Me

- Song Birds

- Spare Moments

- Speak The Truth

- Strong Character

- Strong In Him

- Take Care

- Talking To Jesus

- Tekel

- Tell A Lie

- Temptation

- The Broken Saw

- The Garden Of Peace

- The Peacemaker

- The Praying Girl

- The Prussian Girl

- The Sisters

- The Almond Blossoms

- The Apostle Paul

- The Barefoot Boy

- The Beautiful

- The Beggar Boy

- The Best Riches

- The Big Umbrella

- The Black Lamb

- The Boy At The Gate

- The Boy's Triumph

- The Broken Plate

- The Charmer

- The Child And Butterfly

- The Child's Answer

- The Child's Gospel

- The Circus

- The Cocoa Nut Tree

- The Comforting Hope

- The Contribution

- The Converted Negro

- The Curious Dish

- The Distrustful Bird

- The Dragon Fly

- The Earlier The Easier

- The Example Of Jesus

- The Eye Servant

- The Fall Of Pemberton

- The First Command

- The Five Peaches

- The Flower Fadeth

- The Flower Of Pleasure

- The Friend

- The Golden Pennies

- The Golden Rule

- The Grateful Tiger

- The Hinge Maker

- The Handsome Cloak

- The Heroic Servant

- The Jungle Boy

- The Lamb

- The Last Dollar

- The Liar

- The Little Blind Girl

- The Little Captives

- The Little Loaf

- The Little Swearer

- The Swiss Girl

- The Little Truant

- The Lost Boys

- The Lost Child

- The Lost Fellow

- The Lost Children

- The Man In The Dark

- The Mocking Bird

- The Narrow Way

- The Fishermen

- The Persevering Boy

- The Prayer Girl

- The Poor Slave

- The Prince And Serfs

- The Rebuke

- The Repose Of Flower

- The Robin

- The Signal Gun

- The Sleigh Ride

- The Snow

- The Squirrel Rights

- The Story Of Redemption

- The Strawberries

- The Struggle And Victory

- The Teacher's Return

- The Third Commandment

- The Three Boys

- The Turnover

- The Two Sons

- The Way

- The Well Never Dries

- The Widow's Prayer

- The Widow

- The Widow's Son

- The Wonderful Water

- The Works Of God

- The Worst Being

- They Say

- Thou God Seest

- Three Helps

- Thunder Storms

- The Little Worm Ped

- To The Boys

- To The Young

- Tower Of Repentance

- Traveler

- Tread Under Foot

- Tree Never Fades

- Trot Foot

- True Riches

- True Courage

- Trust The Lord

- Two Little Girls

- Two Faces

- Two Inheritances

- Two Proverbs

- Two Voices

- Unchecked Growth

- Uncle Crisp

- Unsaid Words

- Unseen influences

- Vain Thoughts

- Value Of Perseverence

- Waiting

- What The Clock say

- What God Has Done

- What Have you Done

- What Will Jesus Say

- What Makes A Man

- What Malachi Says

- What Grasshoppers Did

- What To Read

- What Two Apples Did

- When May Children

- Where Is Your Treasure

- Who Are Associates

- Who Prays

- Willie's Faith

- Without Affection

- Woodland Rambles

- Work For Sabbath School

- Yield A Little

- Young Christian Reflection

- The Drowned God

- David Hume

- The Holy Coat

- A Beam

- A Beautiful Answer

- A Beautiful Incident 2

- A Boy's Leisure Hours

- A Brave Boy

- A Coffee Field

- A Curious Instrument

- A Fortified City

- A Fortune Book

- A Glimpse Of Cal

- A Guilty Conscience

- A Happy New Year

- A High Standard

- A Hot Water River

- A Lesson From Snail

- A Little Boy Sermon

- A Little Candle

- A Little Child

- A Little Errand

- A Little Hero

- A Little Self

- A Novel Perfume

- A Plant With No Stalk

- A Pleasant Occasion

- A Prize Character

- A Rich Man

- A Ropewalk

- A Sabbath Stone

- A School Girl

- A Scientific Wonder

- A Sealed Postman

- A Sermon On Light

- A Sermon On Push

- A Sketch Of History

- A Sleigh Ride

- A Strange Ambition

- A Strange Clock

- A Syrian Family

- A Terrific Storm

- A Thorn In The Pillow

- A Visit To London

- A Walking Leaf

- A Wonderful Clock

- A Wonderful Stick

- A Word Spoken

- A Word For Boys

- About Proving

- About Watches

- Absalom's Rebellion

- Acquaint Now Thyself

- Acting From Principle

- After Ahab Died

- Ahab's Wicked Reign

- Ahaz And Hezekiah

- AI

- Alexandria

- Among The Flowers

- Among The Roses

- Amusements

- An Awful Story

- An Important Question

- An Old Man

- Ancient Mounds

- Antiochus Epiphanes

- Antiquity Of Umbrellas

- Archery

- Are You Growing

- Asa

- Asa's Good Reign

- Aunt Lizzie's Story

- Bad Promises

- Bank Note

- Be Prompt

- Be Sure Your Sin

- Be True

- Beautiful Thoughts

- Behind Time

- Benhadad's Defeat

- Bernard Palissy

- Blessed Are Peace

- Blindness

- Butter Making

- Capernaum

- Carmel

- Carried Away

- Changes

- Character

- Children Voices

- Chinese In California

- Chinese Politeness

- Chinese Stories

- Christian Obedience

- Christmas Time

- Chromos

- Cinnamon Trees

- Clean Inside

- Cleopatra's Needle

- Colorado

- Come Inside

- Confidence

- Contemporary History

- Correct Speech

- Cost Of Tobacco

- Covenant

- Daily Bread

- Daisy's Flowers

- Daniel

- David's Flight

- David And Goliath

- David Maydole

- David Numbers The People

- David's Charge

- David's Desire

- David's Sin

- Dead Languages

- Death Of Eli

- Deborah And Barak

- Deliverance

- Demand

- Departure

- Did He Tell A Lie

- Disagreeable Habits

- Discovery Of Gas

- Do You Love Back

- Do You Match

- Do Your Best

- Dreams

- Drifting

- Droll Doings

- Eastern Beds

- Elijah Brings Fire

- Elijah Prays For Rain

- Elijah Raises The Dead

- Elijah Taken To Heaven

- Elise Le Mont

- Elisha's Miracles

- Ella's Garden

- Ellens Key

- Emery Ore

- Esdraelon

- Every Day Heroism

- Exaggeration

- Eyes And No Eyes

- Facts About Varnish

- Faith

- Famine In Samaria

- Filial Love

- First Lessons

- Fitly Answered

- Floating Gardens

- Florie's Birthday

- Follow Copy

- Foolscap Paper

- For Boys

- For Christ's Sake

- For Me

- Fords Of Jordan

- Forgive

- Freedom For Pets

- From History Abraham

- From History Jews Captive

- From History Rome Builds

- From History Rome

- From History State

- From History Jerusalem

- From Sea To Sea 1

- From Sea To Sea 2

- Gedaliah

- George's Reason

- Gideon And The Angel

- Gideon's army

- Girls Look Here

- Glass Garments

- Go Because It Rains

- God's Acre

- God's Care

- God's Life Book

- Gold and Silver Mine

- Golden Moments

- Good Advice

- Good Resolutions

- Grandmother's Visit

- Grandpa's Example

- HALLELUJAH

- Harry's Lesson

- Harry's Stratagem

- Have A Choice

- Herod The Great

- Herrings For Nothing

- History Of Bells

- Hitting The Mark

- Honesty Rewarded

- Honor Bright

- Honor Thy Father

- How Do You Meet

- How Many Were There

- How Rain Is Formed

- How Rubber Shoes

- How Slate Pencils

- How Strong Is God

- How Sunday School

- How The Fuchsia

- How The Months

- How To Be Gentleman

- How To Be Beautiful

- How To Read

- How To See A Seed

- How To Thank

- How To Treat Brother

- Hungry Children Fed

- I am The Shepherd

- I Am Bid

- I Prayed For Them

- Illusions

- In Another Battle

- In The Streets

- In The Sunshine

- Incidents Of Wilder

- Independence Day

- Indian Corn

- Influence

- Iron Swims

- Iron Shod

- Is There A God

- Is Your Note Good

- Israel Cross Jordan

- Israel Multiplies

- It Comes From Above

- It Isn't Mine

- It's Ours

- Jehoshaphat

- Jehu

- Jericho

- Jeroboam Leads

- Jerusalem Destroyed

- Jerusalem

- Jessie's Help

- Jews

- John's Account

- Johnny

- Jonah's Preaching

- Josiah

- Jotham

- Judging Israel

- June

- Just Caught

- Keep A Light

- Keep Thyself Pure

- Keep Your Promise

- Keep His Word

- Kindness

- King And Queen

- King Belshazzar

- Kings Of Judah

- Knocking Knees

- Known By His Walk

- Lamp To My Feet

- Learn To Remember

- Learn To Think

- Learning

- Leaves

- Lesson

- Life's Great Object

- Life A Failure

- Life Of Our Saviour

- Lighthouses

- Listen Carefully

- Little Christians

- Little Margaret

- Little Scotch

- Little Such Things

- 'LL No Trust Ye

- Look Out

- Looking For Papa

- Lucky Friday

- Luther Snow Song

- Mabel's Secret

- Make Home Pleasant

- Make Some Happy

- Make Sabbath

- Make Beginning

- Making Sunshine

- Manasseh

- Manasseh-Josiah

- Manner Of Burial

- Manners

- Maple Sugar

- Marble Block

- Martyrdom

- Maude And Lizzie

- May And Might

- Measureless Love

- Mercy And Wrath

- Milan Cathedral

- Mine And Thine

- Miss Vanity

- Mistakes

- More War

- Mother

- Mourning

- Mount Carmel

- Murmured

- Music

- Naaman The Syrian

- Naboth's Vineyard

- Name

- Nature

- Nature's Spring

- Nazareth

- Nebuchadnezzar

- Nehemiah

- Ninety And Nine

- NO

- Nobleman

- Notes On Bible

- Novel Playhouse

- Novel Reading

- Now Here

- Nutmegs

- Obey Mother

- OH I Forgot

- Oil On Water

- Old Testament

- Only A Pin

- Oranges

- Origin Of Plants

- Origin Of Christmas

- Our Christ

- Our Daily Cup

- Our Blessings

- Our Little Washer

- Our Lord's Miracles

- Our Thoughts

- Over In A Minute

- Overcoming

- Palestine

- Palestine Features

- Palms

- Paper Barrels

- Passages In Garfield

- Patience

- Paul's Lesson

- Pay Your Debt

- Pearls

- Pearl's Thanks

- Perfect Faith

- Perpetual

- Philip And Effie

- Pins

- Pins And Needles

- Plan To Come

- Plants

- Pleasures

- Plums

- Powers Of The Air

- Prayer Answered

- Present Truth

- Presidential Electors

- Prophecy Of Babylon

- Prophet Daniel

- Prosperous Belgium

- Protected

- Proud King

- Province Of Galilee

- Pull Together

- Queer Tom

- Raising Tomatoes

- Ransoms

- Rapids

- Read The Bible

- Real Presents

- Rebellion

- Rebuild The Temple

- Recapitulation

- Rehoboam

- Remember Ebal

- Repentance

- Resolution No 3

- Rest

- Results Of Accidents

- Return Of Jews

- Ride Through Kent

- Right To The Habit

- River

- Rob's Magic Mirror

- Rocky Mountain

- Rome And Britain

- Rosetta Stone

- Royal Guests

- Ruined

- Rural Life

- Sackcloth Ashes

- Samaria

- Samuel And David

- Samuel's Call

- Samuel Reproves

- Samuel's Prayer

- Saul Anointed

- Saul Then David

- Says So

- Scenes Of Galilee

- Scraps From History

- Secret Meeting

- Seed By The Way

- Seed Sown

- Self Respect

- Sewing Aches

- Shall We Pray

- Shut Eyes Tight

- Signal Lights

- Silent Influence

- Silver Smelting

- Simple Kra's Gift

- Sin

- Sitting Up

- Six Months On Ice

- Sketch Of Babylon

- Slide Along

- So How Long

- So Only A Flower

- Soap Bubbles

- Societies

- Solomon

- Some Advice

- Some Day

- Somebody

- Something For Girls

- Something New

- Something To Carry

- Somewhere Blue Sky

- Sowing Little Seeds

- Sowing Time

- Splicing The Ladder

- Standing For Right

- Stars

- Stick To Your Tree

- Story Of Flower

- Strange Food

- Strike The Knot

- Striking

- Sugar Making

- Surnames

- Susie's Exam

- Syrian Army

- Tabernacle

- Talk It Over

- Taught

- Teach The Samaritans

- Teacher Is Hidden

- Tell Your Mother

- Telling The Lord

- Temple

- Tested

- Texas

- That's How

- The Aborigines

- The Accurate Boy

- The Air

- The Anchor

- The Apostle John

- The Baptism

- The Baptist

- The Bible

- The Bible The Root

- The Bird Of Two

- The Birth Of Christ

- The Birth Of John

- The Black Rock

- The Blue Bead

- The Book Of Nature

- The Boyhood Of Jesus

- The Burial Of Joseph

- The Buttes

- The Call Of Matthew

- The Captain Slain

- The Carpet Weaver

- The Celestial Road

- The Child Dyke

- The Clam

- The Climate

- The Color Of Gem

- The Cost Of Care

- The Cousins

- The Crown Of England

- The Dedication

- The Difference

- The Dream Fulfilled

- The Fiery Furnace

- The First Newspaper

- The First Fruit

- The First Miracle

- The First Prayer

- The First Psalm

- The First Snow

- The First Step

- The First Wrong

- The Flight

- The Fresh Hour

- The Garden

- The Gate Shut

- The Giant Sin

- The Gibeonites

- The Gift Of God

- The Gospel Alphabet

- The Great Master

- The Great Wall

- The Gulf Stream

- The Halfway Place

- The Hardest Thing

- The Healed Servant

- The Heart Gardens

- The Holy Land

- The Homes Of Jesus

- The Ignis Fatuus

- The Influence

- The Irish Boy

- The Isle Of Cyprus

- The Jingle Bells

- The Kingdom Divided

- The Land Of Moab

- The Last

- The Leading Hand

- The Left Glove

- The Light

- The Lighthouse

- The Little Baby

- The Little Girl

- The Little Orphans

- The Little Songstress

- The Logic Of Life

- The Lord Knoweth

- The Lord Is God

- The Losings Bank

- The Lost Boy

- The Lotus

- The Maccabees

- The Magnet

- The Man Who

- The Microscope

- The Midnight Sun

- The Milk Tree

- The Moment Of Peril

- The Moon

- The Mount

- The Mysteries

- The Native Of Kilda

- The Natural Bridge

- The Nettle Tree

- The New Dress

- The Nobleman

- The Northern Lights

- The Old Monk

- The Old School

- The Oldest Book

- The Passover

- The Passover 2

- The People Of Arabia

- The Picnic

- The Planet Mercury

- The Preacher John

- The Present

- The Price Paid

- The Privilege

- The Prophet Jeremiah

- The Prophets

- The Pyramids

- The Resurrection

- The Rich Noble

- The River Jordan

- The River Nile

- The Runaway

- The Sabbath Cradle

- The Safe Retreat

- The Sailor Boy

- The Saviour's Invitation

- The School

- The Sea Of Galilee

- The Second Passover

- The Second Temple

- The Seven Wonders

- The Shipwrecked

- The Shunammite

- The Sin Of Lying

- The Skeptic

- The Sleep Of Flowers

- The Snowball

- The Sowing

- The Spring Comes

- The Starry Crowns

- The Stepping Stones

- The Stinging Tree

- The Stone Lamb

- The Sunbeam

- The Testimony

- The Three Sieves

- The Time To Be

- The Time

- The Tongue

- The Traveler's Tree

- The True Riches

- The Twelve Apostles

- The Useful Plant

- The Victoria Regia

- The Visit Of Wisemen

- The Waldensian

- The Water Lily

- The Water Mill

- The Way Effie Helped

- The Whole Class

- The Wilderness

- The Willful Boy

- The Woman

- The Wonderful Asbestos

- The Yosemite Valley

- The Young Gardener

- There Is One God

- These Little Strings

- Thine Is The Power

- This Coal Oil Johnny

- This Is Given

- Though Fearful

- Those Giant Mts

- Thoughtful

- Thoughtless Fun

- Three Hands

- Throne Of Judah

- Time

- Time To Study

- Tis For Love

- To Avoid Bad Books

- To Be Sure

- To Bear Burdens

- To Egypt

- To Galilee

- To Help People

- To Love

- To Smyrna

- Tobacco

- Tommy's Rabbits

- Too Bad

- Too Late

- Touch Of Faith

- Town Of Bethlehem

- Trip To California

- Triumphal Arches

- Troubles

- True Boy

- True Gentlemen

- Trust In Jesus

- Truth

- Try It

- Two Good Hands

- Two Of Ned's Rudders

- Two Poisons

- Two Ways

- Tyre And Sidon

- Unbelief

- Under The Sea

- Valley Of Petra

- Vast Colorado

- Very Fast

- Very Good Habit

- Very Sad Lesson

- Victory

- Visit To A Poet

- Visit To Nazareth

- Vitality Of Seeds

- Walter Entertained

- Want God's Pictures

- Watches

- Waves

- Wayside Scenes

- Wait Till You Know

- Wardrobe

- Water

- Well

- Well Do You Know

- Westward Bound

- Wharf

- What A Brave Boy

- What Came Of It

- What Have I Done

- What Is Sweeter

- What Is Your Copy

- What Kelsey Learned

- What Made Two--

- What The Rain Taught

- What To Give

- Wheat

- Wheat Fields

- When Knives

- When The Last Rays

- Where Alsatian

- Where Are The Cliff

- Where Is My Influence

- Where Is That Boy

- Where Jesus Taught

- Which Seed Are You

- Which Is Penitent

- Which Way Do You

- Who Will Be Ready

- Whom Can You Trust

- Why Are There Three

- Why Did He Learn

- Why Was Ethel

- Why Not Keep

- Why Was Christ

- Wicked Thoughts

- Wide Circuit

- Wild Flowers

- Wilderness

- Will And A Way

- Will He Succeed

- Will

- Willie's Violets

- Windsor Castle

- Wish

- Wolf Monument

- Wonderful Clock

- Wonderful Mother

- Wonderful Sights

- Wood

- Words To Girls

- Words To Boys

- Work

- Work Attention

- Work Before Play

- Work For All

- Work Footprints

- Working Dreaming

- Worthy Humble

- Wreckers

- Wycliffe

- Yearning For Jesus

- Yes My Grace Is

- Yet Not Useless

- Yosemite Valley

- You Better Watch Out

- You Can Consider

- You Are A Little

- Your Parents

- Your Word Is Sufficient

- Youth

- Youth Instructor

- Youthful Manners

- Zest Of Rice

- A Carpet

- A cross-look

- A grape-gatherer

- A dripping-well

- A Queer Way

- A Single Worm

- A Very Bad Habit

- A Walled Lake

- A Waterfall

- Abideth Forever

- Alice's Talent

- Curious Plants

- Curious Watches

- Five Cents

- Gethsemane

- Heal The Paralytic

- How Clinton

- How Children Play

- How Tower Clocks

- Jerusalem Now

- Still The Tempest

- John's Object Lesson

- Lot's Wife

- Mozart

- Origin Of Names

- Patience And Charity

- Perfect Trust

- Pleasant

- Power Of Voice

- Prove It

- Remember The Sabbath

- Resisted

- She Could

- Sketches Holy Land

- Tea Gardens

- The Clock Ticking

- The Dead Sea

- The Death Of John

- The Death Of Presidents

- The Disciples

- The Great Cataract

- The Gypsies

- The Japanese

- The Mustard Tree

- The Northern Sea

- The Orphan's Friend

- The Phoenician Coast

- The Power

- The Regalia

- The Thousand Islands

- True Politeness

- We Wanted To Come

- What Nettie Needed

- What The Flowers Said

- Why Everybody Is Cross